About the LevelUp series: At The Markup, we’re committed to doing everything we can to protect our readers from digital harm, write about the processes we develop, and share our work. We’re constantly working on improving digital security, respecting reader privacy, creating ethical and responsible user experiences, and making sure our site and tools are accessible.

Last October, a Markup investigation found that Amazon Ring’s social platform, Neighbors, funnels suspicions from residents in Whiter and wealthier areas of Los Angeles directly to the police. Our reporting showed that more than 2,600 police and close to 600 fire departments in the U.S. have partnerships with Ring, the popular doorbell camera company that was acquired by Amazon in 2018.

We teamed up with five students at the Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism at CUNY (full disclosure: Craig Newmark is also a Markup funder) during the investigation: Randi Love, James O’Donnell, Ariana Perez-Castells, Natalia Sánchez Loayza, and Paisley Trent. I also wanted to make sure we made a special effort to recognize the students’ contributions to this project. In addition crediting them on the investigation when we published, since I was a Pulitzer Center fellow when I organized this FOI audit, I was able to use my fellowship budget to offer each student $500 for their work.

Together, the students sent public records requests to 25 different police departments that had partnerships with Ring in some of the country’s biggest cities. This process is called a public records audit, which an expert once coined to me on a call, because documenting what happened allows us to see which police departments were complying with local laws.

The Markup (like many other organizations) uses public record requests as an important investigative tool, and we’ve published tips for fellow journalists on how to best craft their requests for specific investigations. But based on where government institutions are located, public record laws vary. Generally, government institutions are required to release documents to anyone who requests them, except when information falls under a specific exemption, like information that invades an individual’s privacy or if there are trade secrets. Federal institutions are governed by the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), but state or local government agencies have their own state freedom of information laws, and they aren’t all identical.

Public record audits take a step back. By sending the same freedom of information (FOI) request to agencies around the country, audits can help journalists, researchers and everyday people track which agency will release records and which may not, and if they’re complying with state laws. According to the national freedom of information coalition, “audits have led to legislative reforms and the establishment of ombudsman positions to represent the public’s interests.”

The basics of auditing is simple: Send the same FOI request to different government agencies, document how you followed up, and document the outcome. Here’s how we coordinated this process with student reporters.

Be clear about your goals

When Ring first launched, there was a lot of insightful reporting about how the company was actively courting police departments for partnerships. Five years later, our goal was to get a better understanding of what these partnerships looked like.

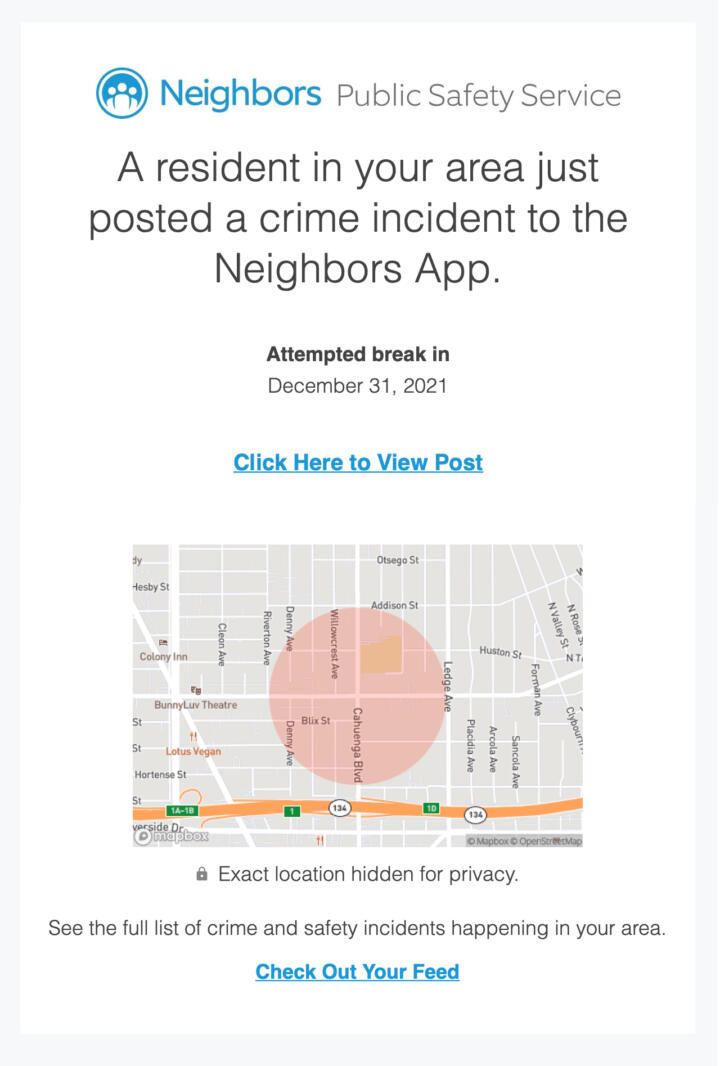

From previous reporting, we knew that police would sometimes receive email alerts about crimes posted in a neighborhood:

These emails did not contain any information that would need to be redacted, since it doesn’t have any identifying information. A previous public records request to the Brookhaven Police Department showed that there were many emails from Neighbors that we could ask for and that police departments could easily export emails in electronic formats.

For this project,our goals were:

- To unearth new information about the relationship between police departments across the country and Ring/Neighbors

- To find better ways to communicate with FOI officers about technology, to successfully request materials that are electronic and not PDFs

- To gather information about FOI officers, who may be in charge of emails and data servers, and how each department handled our request

We decided to request the Neighbors emails in two formats (.eml and .msg) because that’s the format native to email clients like Outlook. But since these formats are not well-known, students had to find ways to explain them to FOI officers and to give them clear instructions on how to export emails to these formats.

Through this process we also learned about other formats that may be helpful to request in the future: .mbox and .pst files which are similar to .eml and .msg, but instead of containing individual emails, .mbox and .pst folders allow FOI officers to download entire folders of emails.

Start with a Template

For each of the 25 police departments, students used a shared Google spreadsheet to gather information about the person in charge of emails or servers, the email and phone number of FOI officers, and local media reports on the relationship between police departments and Ring/Neighbors.

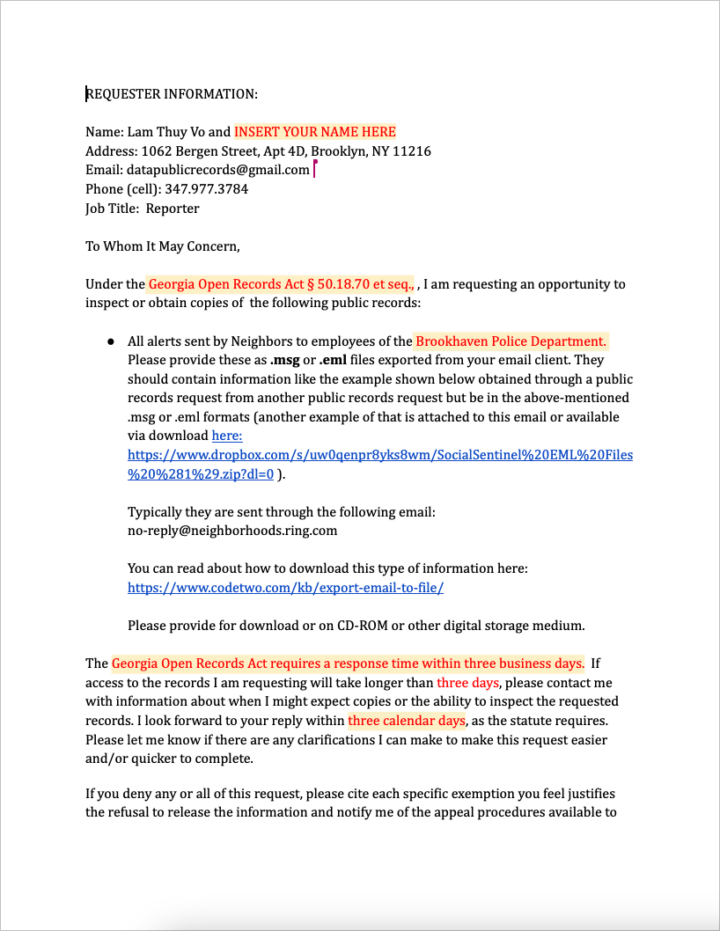

The students then wrote up public records requests, tailoring the language to state-specific laws and putting their names and my name as the contacts on the letters. In their requests, students asked each department for all alerts sent by Neighbors to employees of the department as .msg or .eml files exported from their email client. Request language was based on my previous successful public records request to the Brookhaven Police Department, which led to the release of several hundred records.

Share the Same Logins and Email

Working as a team of six (myself included) required us to be coordinated and structured in our approach. Throughout the project we communicated via a Signal group, exchanging tactics that helped us get progress with our requests, such as asking family members or friends to help file public records requests in states that require filers to be local residents.

We also all used the same email address to send public records requests or to create logins and passwords for government portals, where many police departments required them to file requests. We also shared passwords and logins using the platform 1Password, which is free for journalists.

This way, any student could easily follow up on any public records request that the team sent out. Since we were also using one email address to file all our public records requests—everyone could see how varied the responses were and could learn from one another.

Only seven out of 25 departments provided data in response to our requests, and since the Los Angeles Police Department gave us the most comprehensive data in the formats that we had requested, we dug further into Los Angeles, which eventually became the center of The Markup’s investigation.

Pick a Reasonable Timeline and Track What Happens

We capped the timeline for the FOI audit to eight weeks. This ensured that the requests and follow ups could be done within a 15-week class. Eight weeks also seemed like a fair amount of time for FOI officers to look into the issue, understand it, and find ways to work with their IT department or other colleagues to export the data.

After the 8-week period of filing and communicating with FOI, the CUNY students and I summarized various parts of the process in a structured format.

This Google spreadsheet template shows the different types of information that we tracked across all 25 FOI requests, how police departments responded, how long it took for them to comply, and what information was released.

Resources and Templates

If you’re interested in involving students or any kind of team in a public record audit, these are the documents and templates I used for my five students.

Preparation for filing public records:

- A detailed methodology for students

- A template for collecting information about their assigned police department

Filing and tracking requests:

- A FOI template

- A FOI request tracker template that includes links to sample language for public records requests in all fifty states

If you’re a journalist or researcher looking to do a similar project, send me a note, and I’d be happy to share detailed results of our FOI audit.

Update: Jan. 24, 2024

We added additional details about how Lam credited and compensated students, so readers can use Lam's work as a model to work with their own team partners.