The Markup, now a part of CalMatters, uses investigative reporting, data analysis, and software engineering to challenge technology to serve the public good. Sign up for Klaxon, a newsletter that delivers our stories and tools directly to your inbox.

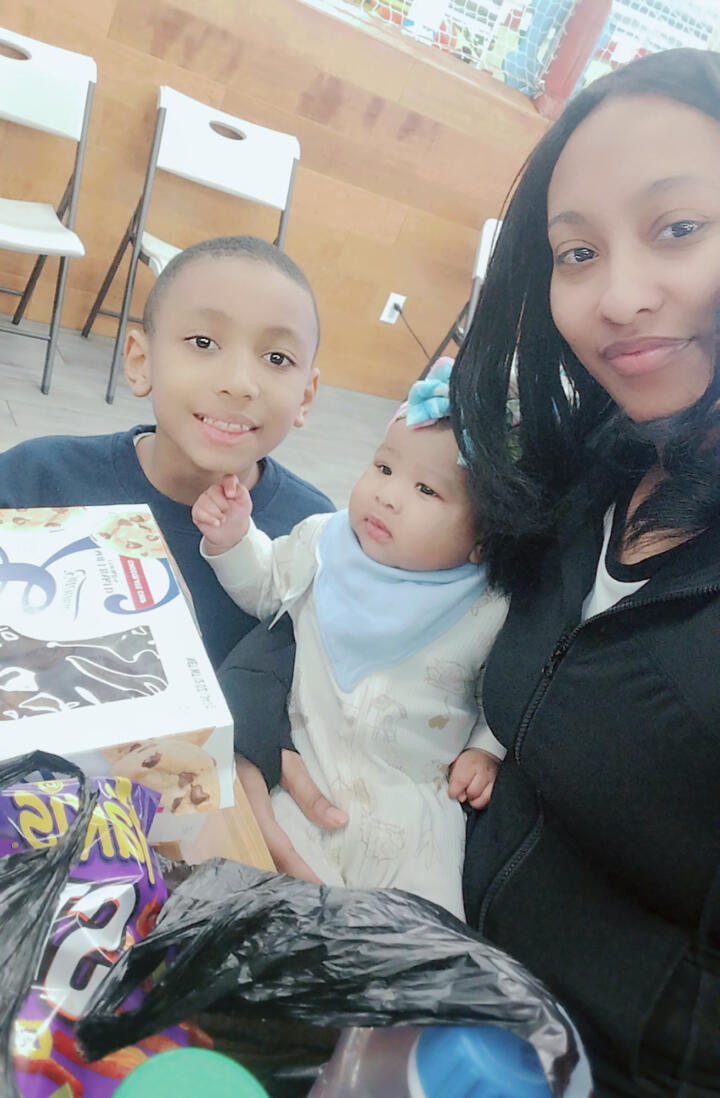

Karlena Hamblin was sitting on a stool in her Brownsville, Brooklyn apartment waiting for the Administration for Children’s Services to knock on her door for a weekly check-in. She’d just fed her infant daughter, who she held cradled in her arms.

ACS, which is responsible for investigating child welfare in New York City, had been watching her and her family since she was three months pregnant, when the agency held a pre-birth conference to talk over her family’s future. “The baby’s not even here yet and you’re already talking about removing her?” she said. “I didn’t even know what I was having yet.” She sobbed at night from fear.

Now, investigators check her daughter for signs of abuse or neglect, and could report anything they learn to a family court judge. Hanging over every visit is the chance that a misstep leads to her losing her daughter, who’s now just a few months old, to the foster care system.

“I’m always worried,” Hamblin said. “I get more anxious around any court date, and even though I tell myself, ‘No, I’m not doing nothing wrong, I don’t have nothing to hide,’ it’s like I’m programmed to be scared because I’ve been afraid since day one.”

Hamblin has a good idea why she’s under surveillance. She grew up in foster care. Shortly after aging out, she got pregnant and later, she says, developed symptoms of postpartum depression. She checked herself into the psych ward while her sister cared for her infant son. She lost him to foster care in 2017.

But ACS has another way to place parents under the closest scrutiny, one that few people in and around the system even know about — an artificial intelligence tool. The Markup has learned that in recent years, ACS has been using an algorithm intended to score the chances a child will be severely injured in their household.

The tool, first launched in 2018, was developed by an internal data team at the agency, the Office of Research Analytics. The families ranked highest risk by the system face additional screening, with a review from a higher-level specialist team that could spark home visits, calls to teachers and family, or consultations with outside experts.

According to documents obtained by The Markup, the AI-powered system uses 279 variables to score families for risk, based on cases from 2013 and 2014 that ended in a child being severely harmed. Some factors might be expected, like past involvement with ACS. Other factors used by the algorithm are largely out of a caretaker’s control, and align closely with socioeconomic status. The neighborhood that a family lives in contributes to their score, and so does the mother’s age. The algorithm also factors in how many siblings a child under investigation has, as well as their ages. A caretaker’s physical and mental health contributes to the score, too.

While the tool is new, both the data it’s built on and the factors it considers raise the concern that artificial intelligence will re-inforce or even amplify how racial discrimination taints child protection investigations in New York City and beyond, civil rights groups and advocates for families argue.

Joyce McMillan, executive director of Just Making A Change for Families and a prominent critic of ACS, said the algorithm “generalizes people.”

“My neighborhood alone makes me more likely to be abusive or neglectful?” she said. “That’s because we look at poverty as neglect and the neighborhoods they identify have very low resources.”

Even those who work closely on child welfare issues in the city often don’t know ACS’ algorithm exists: several lawyers, advocates, and parents learned about it for the first time from The Markup, and those who did know about it were unaware of the factors that contribute to a score. Hamblin likely will never get confirmation how she was scored, or whether she reached the threshold for additional scrutiny into her daughter’s case. ACS tells neither families, their attorneys nor its caseworkers when the algorithm flags a case.

“We get discovery in individual investigations and prosecutions when we represent parents, and nothing in the discovery we get suggests or implies, and certainly doesn’t lay out, use of any of these tools,” said Nila Natarajan, associate director of policy and family defense at Brooklyn Defender Services, which represents families against ACS in family court.

Documents suggest that ACS has considered some of the same pitfalls of the tools as family advocates. “Using poor or biased proxies can lead to the wrong resource allocations, cause harm to families, and perpetuate systemic biases and disproportionality,” a technical audit of the system by the agency obtained by The Markup acknowledges. The internal audit found that the data used by ACS to train the algorithm likely included at least “some implicit and systemic biases” baked in, as some families are investigated at disproportionate rates.

The report still concluded that the system more accurately predicted which past cases ended in harm than criteria the agency had chosen in the past, like whether the child was under one year old or their caretaker had abused drugs and alcohol.

Marisa Kaufman, a spokesperson for ACS, acknowledged that “no predictive tool is entirely free from bias” but that the agency has attempted to mitigate those problems by using a mix of current and past data to prevent relying on “historical patterns,” and uses audits to “examine whether the model performance is similar for all race/ethnicity groups and whether the model is making similar predictions for children with similar historical backgrounds.”

She said ACS hasn’t studied what effect the additional review has on the outcome of a case, including whether a child is ultimately removed from a home. It’s not feasible to design such an experiment, Kaufman said. She pointed out that, in general, only a small fraction of cases end with removal, and that decisions about interventions are decided by staff, and never directly by a machine.

ACS disclosed its use of the tool after New York City required city agencies to list their use of automated tools in a series of yearly reports, first announced in 2018. In the reports, ACS briefly noted its use of the child safety algorithm and one related tool. It was one of 16 disclosures within the initial report from agencies across the city.

A separate 2023 report from the New York State Comptroller reviewing algorithmic tools also mentioned the ACS algorithm as one of several systems being used by other city agencies, including the NYPD. “NYC does not have an effective AI governance framework,” that report concluded.

The algorithm was otherwise implemented with little public scrutiny. In response to a public records request, The Markup received the agency’s internal technical audit of the algorithm, which reveals how ACS caseworkers use the algorithm and the potential biases built into it.

Because of both social factors like poverty as well as possible bias in how cases are reported, investigated, and judged, families of color are far more likely than their white peers to face an ACS investigation, according to the American Civil Liberties Union, which has studied rates of investigation across different demographics through mandatory ACS disclosures that include the races of families facing investigation. Even if a case is ultimately dropped, Black families are more likely to have child welfare services called to investigate them, for example, and calls to ACS contribute to a family’s score. The algorithm, according to a report obtained by The Markup, does not explicitly use race to score families, but uses “variables that may act as partial proxies for race (e.g., geography)” to make its decisions, including a family’s county (or borough), zoning area, and community district.

Like Hamblin, other parents who spoke to The Markup wondered whether they’d been involved in a case that had been flagged for review by AI, or were troubled at the idea of an algorithm pulling data from their case at all.

Jasmine Mitchell, a 39-year-old singer and CUNY film student, said she threw up from anxiety when ACS first knocked on her door and spoke to her and her daughter in 2021, and was stunned when it happened again a year later. Both investigations were eventually deemed unfounded, she said, and she blames the first on an ex-boyfriend, the second on a disgruntled business partner.

“I’m still in the database,” she said. “It feels like there’s this permanence to it even though both of my investigations were unfounded.”

Most calls to ACS are eventually deemed unfounded. But the resulting investigations can be a terrifying form of harassment against a family, as they potentially spend months with the threat of their child being removed from their home.

“I don’t think the algorithm is unbiased,” Mitchell said. She lives in Flatbush, a culturally diverse neighborhood, and is concerned about what that would mean for her.

“I could only imagine that alone would increase my score,” she said. “I just find it all very disturbing.”

How the Tool Works

ACS opens tens of thousands of investigations each year. Those investigations are a crucial part of protecting vulnerable children from harm, ACS and other child welfare agencies argue. When they fail and a child is harmed, ACS faces the blame.

The agency documents note that ACS can prioritize only a fraction of those cases – 200 or 300 a month – for review, a process the agency calls “quality assurance.” The agency developed the algorithm to decide which cases to review. The tool computes data from hundreds of factors to determine a risk score, and cases above a certain risk are flagged for additional scrutiny.

Along with geographic and demographic variables, the score also factors in whether a family has dealt with ACS in the past, including whether caseworkers have found previous injuries to a child. The number of calls the agency has received about a child, including their length in minutes, is also used.

If a family is flagged by the algorithm for quality assurance review, a senior specialist may hold an “action meeting” with investigators on a case, and direct them to take action they otherwise might have skipped. Kaufman, the spokesperson for ACS, said that direction can include “interviews with family members and collateral contacts; and, in some cases, service referrals, consults with Family Court Legal Services, and clinical experts.”

Only a tiny number of cases lead to a child being severely harmed, meaning the algorithm’s predictions about hundreds of cases “are more likely to be incorrect than correct,” according to ACS’ internal audit.

In one way or another, Hamblin has spent her entire life with ACS oversight. She grew up in foster care herself. Now, the 29-year-old is raising her daughter in a Section 8-subsidized apartment in Brownsville, among the poorest neighborhoods in New York City. The case files from her first child are sealed from public view, but Hamblin shared summaries of ACS meetings about her cases.

The documents she provided noted “a pattern and history of mental health illness” with previous diagnoses including bipolar disorder, borderline disorder, and suicidal ideation.

Hamblin says she was under extreme pressure and in a dark place at the time, but that she’s improved, and the documents seem to bolster that. They note that she “advocates well for herself and her children” and that she’s helped by her boyfriend. “The family has support from extended family and friends,” according to the documents.

She continues to see a therapist. Her son, now 8 years old, remains in foster care, while she gets two hour-long, supervised visits with him per month.

“They target you from the minute you step out of foster care,” Hamblin said. “They have this microscope on you, and for them to build a case based off your prior records of you being in care—it’s not right. It’s like I never had a chance to really feel freedom. Like I’ve been under their watch since birth and I’m still under their watch.”

ACS isn’t the only place child welfare analytics are being tested and used. In the past decade, state and local jurisdictions have been increasingly receptive to the idea of using data to predict injury to a child. Across the country, similar tools are now either being explored or actively in use.

Those projects can be politically fraught. In California, for example, Los Angeles county began piloting a risk-evaluation system in 2021. Last year, the county said it had found no increase in racial bias from the tool during the pilot and would permanently adopt its use.

But at the state level, another project was shelved after testing. In 2016, as documented by The Imprint, an outlet focused on youth and family news, California launched a pilot analytics program meant to prioritize the highest-risk calls to its intake system. The pilot continued for three years, but the state eventually moved away from the project. A report by the state obtained by The Imprint concluded that the tool wouldn’t keep kids safer and could lead to more racial bias in the system.

Most famously, an algorithm used in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, is used by social workers to decide which cases to investigate. In 2023, The Associated Press reported that the tool was under Justice Department scrutiny for potential civil rights violations.

The algorithm ACS uses to review cases is trained to look for parallels between cases from 2013 and 2014 that ended in tragedy, with a child being severely harmed. But those cases don’t represent a neutral data set: Black families are far more likely to face ACS investigation, and generally Black families can face additional scrutiny of injuries than white families in similar circumstances.

In New York City, Black families are reported to ACS at seven times the rate of their white counterparts, and are 13 times more likely to have a child removed. A report from the New York Civil Liberties Union found that 41 percent of the time formal family court cases are filed, they’re against a Black parent. Only six percent of the cases ACS files are against white parents. In the past, the agency has broadly acknowledged racial disparities in child welfare investigations and says it has worked to close the gaps.

Despite Black people being only about 23 percent of the population in New York City, the ACLU report found, Black children make up 52 percent of children removed from their home without a court order.

Civil rights advocates like the ACLU and attorneys who work on behalf of parents worry that algorithmic tools would simply automate past problems.

“ACS has offices in some neighborhoods and not in others,” said Jenna Lauter, policy counsel at the New York Civil Liberties Union. “The over-surveillance of some communities and some geographic areas leads to much more involvement, which is going to skew the data,” Lauter said.

There’s a complex relationship between race and poverty at work, but a 2020 draft report commissioned by the agency, obtained by advocates and published in 2022, included interviews with ACS staff explicitly saying the agency tended to be more punitive toward Black families in the system. The report found that ACS caseworkers believed the agency was unfairly targeting Black families, contributing to a “predatory system” that treats families of color as inherently suspicious.

The New York State Bar Association said in a 2022 report that the system in the state was “plagued by racism, with children and families receiving vastly different treatment depending on the color of their skin.”

Hamblin, who is Black, wonders whether the algorithm may have shaped her interactions with ACS. “Just having a background of ACS in your life as a child, it could be used against you when you’re older,” she said.

Some lawmakers and advocates have said the disclosures agencies have to make for AI tools don’t go far enough, and are pushing for more transparency and oversight. Councilmember Jennifer Gutiérrez has proposed a bill that would create external teams for overseeing the implementation of automated tools.

“These tools aren’t neutral—they can reinforce systemic biases and fundamentally affect people’s lives for decades,” Gutiérrez said in an emailed statement. “The stakes are just too high to not be prioritizing oversight.”

The NYCLU supports state-level legislation called the Digital Fairness Act, which would create both new data privacy and civil rights protections. Under the act, government agencies in the state would be required to undergo a civil rights audit before deploying automated decision-making tools. People who had an automated tool used on them would be informed and allowed to contest the decision.

Hamblin, for her part, is trying to look ahead. As she sat in her apartment, a caseworker called. They’d have to reschedule. Another day alone with her daughter until the caseworker’s next visit and the next court date, and more anxiety for her family. “I’m not doing anything wrong so I shouldn’t have to be living in fear or in guilt,” Hamblin said. “What am I doing wrong?”

While she faces a continuing investigation into her daughter, she’s still fighting for her son in family court. In the meantime, she sees him for visits, and the two children recently met. But if the automated form of scrutiny is distant and invisible, human judgment is always there, even on those family visits. The moments with both children are filled with fear, as she worries whether she might be accused of holding her baby the wrong way, or otherwise having her parenting judged, found wanting, and documented in a file.

“Trying to stay positive keeps me alive,” she said. “But if I just keep letting the negatives pour over me, then I just wouldn’t be able to function.”