Following a recent Markup investigation revealing a secret Google Ads blocklist that hides Black Lives Matter YouTube videos from advertisers—but allowed them to find videos related to “White lives matter”—some small YouTube creators have pledged to leave the platform.

“I will not post any further content on the platform,” Carrie the One, a drag queen and YouTuber with a few dozen followers, said in an email. “I hope that by walking away from YouTube, we can inspire others to join us and put enough pressure on them to change course and do better for all of us.”

“I understand it’s one of the largest media sharing sites,” wrote another streamer who goes by the name Jambo and is mostly on Twitch, “but morals matter, and theirs are not for me.”

Both said that the decision was not hard for them because they hadn’t dedicated much time to YouTube content and didn’t depend on its ad revenue for their livelihood.

Google would not comment on the defections.

Google the Giant

Google Blocks Advertisers from Targeting Black Lives Matter YouTube Videos

“Black power” and “Black Lives Matter” can't be used to find videos for ads, but “White power” and “White lives matter” were just fine

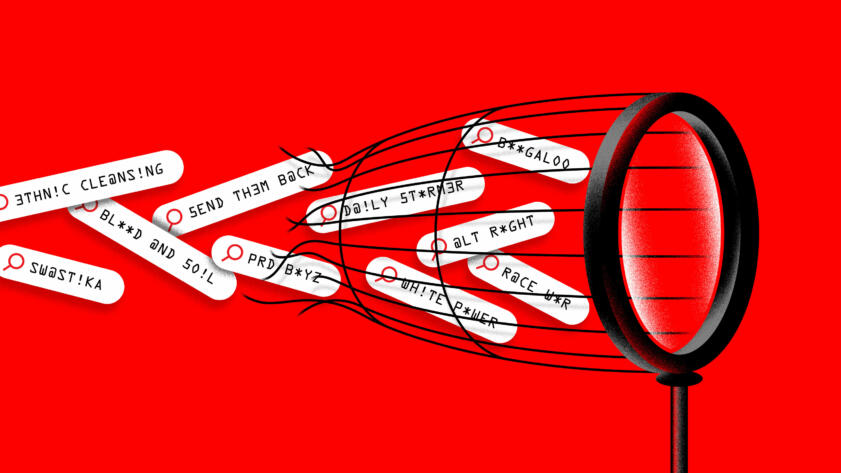

The Markup’s two-part investigative series, published earlier this month, dug into the Google Ads portal that allows advertisers to pick specific YouTube videos and channels for their ads. We found that Google’s blocklist missed most of the hate terms and slogans we checked but blocked equivalent social justice terms.

When we took our findings to Google, the company blocked all but three of the hate terms, but it also increased exponentially the number of social justice terms it blocked for ad searches, eliminating advertisers’ ability to search for 83 percent of the terms on our list, including “Black excellence,” “civil rights,” and “LGBTQ.”

The Markup also found discrepancies in how different religions were treated. When we first tested the portal last November, we found that terms like “Muslim parenting” and “Muslim fashion” were blocked for searches, whereas “Christian fashion” and “Christian parenting” were not—nor were the anti-Muslim hate terms “white sharia” and “civilization jihad.” Rather than lift its ban on phrases containing “Muslim,” Google Ads now also blocks those and other innocuous words in combination with “Christian,” “Buddhist,” and “Jewish.”

As the investigation traveled on social media last week, with thousands of people sharing posts about it, dozens tweeted that they’d had enough and would quit the platform.

We spoke to eight YouTubers who said they were quitting, each with relatively small followings of less than 2,000 YouTube subscribers apiece. They said their decisions to leave the platform reflect a desire to push back at a powerful tech company they believe has done a poor job of listening to their concerns.

Google the Giant

Google Has a Secret Blocklist that Hides YouTube Hate Videos from Advertisers—But It’s Full of Holes

Many well-known White supremacist and White nationalist terms and slogans were not blocked

“I was pretty disgusted that a platform would use such thinly-veiled tactics and exhibit such overt disregard for the experiences and voices of marginalized folks,” Carrie the One said in an email. “We know that racism, homophobia, transphobia, xenophobia, and islamophobia exist and thrive within the systems and structures that our society operates within, but to see those same forces INTENTIONALLY employed by a platform that claims to protect the same folks they are targeting was more than I felt like I could tolerate.”

Google would not respond to The Markup’s questions for the original investigation about why terms like “Black Lives Matter” were blocked—or why it expanded the block.

In response to questions for this story, Google spokesperson Christopher Lawton said in an email: “We know that many brands want to reach audiences who are interested in social justice causes and we want our creators who make videos about these topics to thrive on YouTube.”

He added that YouTube “videos about topics like Black Lives Matter, Black culture and Black excellence, can and do monetize on YouTube, along with topics related to a wide range of social justice issues,” meaning that if advertisers can find these videos despite the block, the videos themselves can run ads.

Graham Jenkins, a video game streamer who uploads on the channel 170Out, said the revelations in The Markup’s investigation pushed him over the edge.

“It’s been on my mind to move from YouTube for a little while now,” Jenkins said in an email. “This isn’t the first time that YouTube has blocked phrases like this but allowed right-wing content to stay unchallenged. I think there was an issue where they blocked LGBT content previously, but are quite happy to allow anti-LGBT videos to remain untouched.”

He was referring to research in 2019 by a group of YouTube creators that showed the platform was systematically demonetizing videos that contained LGBTQ content. YouTube was also criticized for knowingly leaving homophobic content accessible on its platform.

Jenkins said he would stop uploading new content to YouTube as soon as he found another platform that is free for videos of any length.

That might not be so easy. Other YouTubers told The Markup that the platform’s massive reach and ease of use made the choice to stop posting there more difficult.

Sadly, there are currently not any other strong distribution options out there to compete with YouTube

Glam Shatterskull

“Sadly, there are currently not any other strong distribution options out there to compete with YouTube,” said a streamer who goes by the handle Glam Shatterskull and previously posted video gaming content to the platform.

“I would love to see Twitch flesh out its video production offerings,” he said. “In the meantime I will most likely be building out my own website to host video content.”

These content creators weren’t the only ones with harsh words for Google following revelations about its advertising blocklist.

The method Google used to add previously unblocked terms to its blocklist in response to our investigation makes future similar watchdog reporting impossible.

The blocked terms are now indistinguishable in the code from the responses the portal gives for gibberish. Because we now cannot know for certain which terms are blocked, as opposed to the platform not finding any related videos, Google has shielded itself from future scrutiny of its keyword blocks on Google Ads.

This didn’t sit right with Sen. Ron Wyden (D–OR), who authored legislation in 2019 that sought to require tech companies to audit their algorithms for bias.

“Google clearly has a lot of work to do to block hateful videos from advertisers,” said Wyden, who said he plans to reintroduce the bill. “Hiding how it screens those videos is exactly the wrong way to respond to legitimate reporting.”

Lawton, the Google spokesperson, declined to comment on Wyden’s criticism.