My phone, like most people’s, is a gateway to a massive amount of information about me and people I’m close to. Someone holding it in an unlocked state would be able to see years of call records, chat transcripts, and emails. They could browse through every photo I’ve taken in the last decade and read summaries of my recent doctor visits, including any medications I was prescribed.

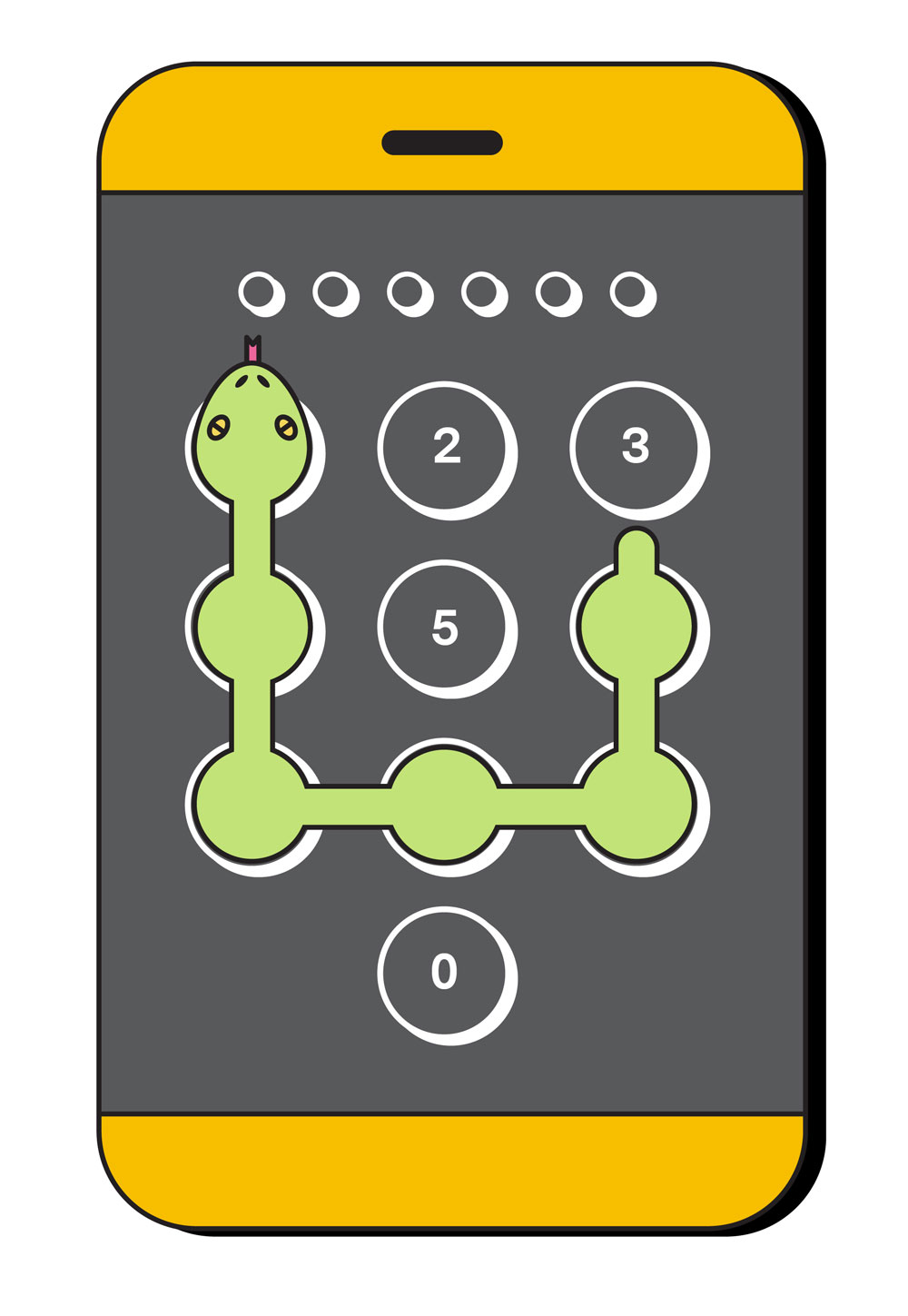

I don’t want anyone I don’t know—especially in law enforcement—seeing that information. That’s why I use a passcode to lock my phone.

The Fifth Amendment and its protection against self incrimination prohibits the police from forcing me to tell them my passcode. Or, at least, it probably, mostly does, depending on where and how I’m asked. The Utah Supreme Court upheld that right in December, but the Illinois Supreme Court ruled the other way just a month earlier.

It’s a disagreement that will probably end up being resolved by the Supreme Court.

One thing most courts do agree on: Law enforcement can require me to unlock a device with my fingerprint or face. It’s the difference between revealing the contents of my mind (my passcode) and giving up physical evidence (my body). The same reasoning applies to a physical safe: you can be compelled to surrender the key that unlocks a safe, but not the combination.

I recommend reading the Minnesota Supreme Court’s opinion in State v. Diamond if you want to dig into the legal arguments.

To switch to using a passcode on an iPhone, check the “Passcode” section of your Settings (it may be called “Touch ID & Passcode” or “Face ID & Passcode”). To start using a PIN, pattern, or password on an Android phone, check the “Security” section of your Settings app and look for “Screen lock.”

Update, April 22: On April 17, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit ruled that the California Highway Patrol did not violate a man’s rights when they forced him to use his thumb to unlock his phone at a traffic stop. As Ars Technica reported, the court held that the compelled thumbprint “required no cognitive exertion, placing it in the same category as a blood draw or a fingerprint taken at booking.” The video, photos, and map data the CHP officers saw on the man’s phone led them to an apartment where they found illegal drugs. Though my recommendations in this article would not have helped this individual—he was required by the terms of his parole to “surrender any electronic device and provide a pass key or code”— the reasoning behind the ruling against him shows they are still good advice for anyone without such restrictions.