On a typical afternoon in The Before Times, the Cherokee Public Library in Cherokee, Iowa (pop. 4,900), would be full of kids. A chatty crowd of three or four dozen middle- and high-schoolers would hang out, do their homework, and socialize in the library’s computer lab—either using one of the library’s public desktops or Chromebooks, or connecting with their own smartphones to the fast Wi-Fi.

Broadband access is rare in Cherokee, said Tyler Hahn, the library’s director; most homes have either hotspots that rely on spotty cell service or satellite access that goes out every time the weather shifts. About 40 percent of school-aged kids have no internet access at home at all, he said.

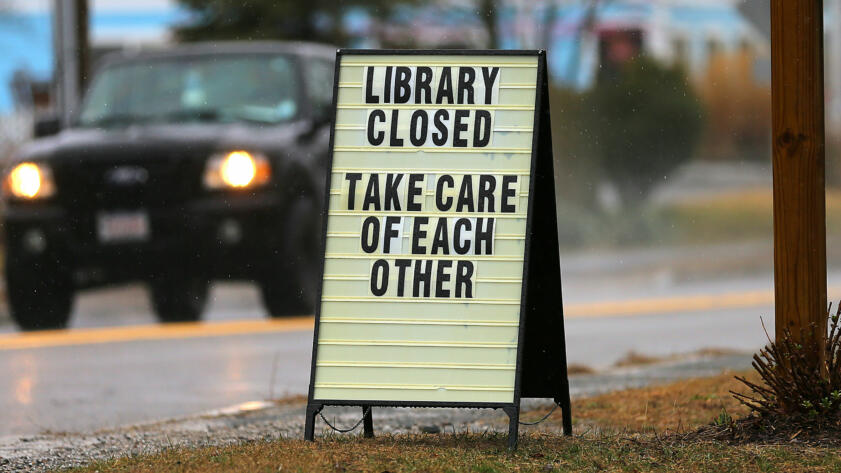

Since COVID-19 forced the library to close in mid-March, the computer lab is empty. But the library is still many residents’ most reliable source of connectivity to the digital world.

Kids sit scattered in the library’s parking lot with phones or video game devices, catching some of the Wi-Fi outside that’s now left on 24/7.

And Hahn spends his days trying to help some older patrons get online by shouting instructions to them through the library’s windows.

Hahn spends his day … shouting instructions to patrons through the library’s windows.

“We have a lot of people who switched from shopping in stores to using Amazon for the first time in their lives,” said Hahn. “Through the window, we were walking them through the steps.”

People have also come to the library to ask Hahn for the phone number to call to apply for unemployment benefits, since they can’t look it up online themselves, he said. They’ve dropped dollar bills through the book slot to pay for printouts of forms.

“It’s been completely bizarre,” said Hahn.

Libraries are still just about the only place in America anyone can go and sit and use a computer and the internet without buying anything. All over the country, library closures during the pandemic have highlighted just how many people have no dependable source of internet on their own.

People in Rural Areas Are Less Likely to Have Access

Percent of Americans who say they have broadband internet at home

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

2000

2005

2010

2015

2019

According to a Pew survey published last year, less than two-thirds of Americans in rural areas have a broadband internet connection at home. Among Americans with household incomes below $30,000, four out of 10 don’t have a computer, and three out of 10 don’t have a smartphone.

Digital disparities are particularly stark in rural areas, but even the most-connected cities aren’t immune. A survey by the New York City Bar Association last month found that only 6 percent of the city’s homeless shelters have internet access. On the first day of the New York City public school district’s remote-learning program, more than 20,000 school-age children were living in the city’s shelters, according to CityLimits.

“We’ve long known at the library how hard it is to be at the wrong end of the digital divide,” said Linda Johnson, CEO and president of Brooklyn Public Library, “but this pandemic has shone a spotlight on it like never before.”

Librarians, well aware of their role, have been finding creative ways to get Wi-Fi to the underconnected areas of their cities and towns, and to help get their less digitally literate patrons up to speed.

A majority of libraries across the country are boosting their Wi-Fi signals and keeping them on all day and night, according to a Public Library Association survey in March. There are roving Bookmobiles pumping Wi-Fi throughout surrounding neighborhoods, says Marijke Visser, senior policy advocate at the American Library Association (ALA), and one library in Arkansas is starting to expand its Wi-Fi coverage by partnering with fire stations to install extra routers there.

Wi-Fi hotspot lending programs are also proving vital. New York City and Chicago libraries have been lending out hotspots for years to anyone who wants them. Seattle’s public library system now has 1,000 hotspots to lend, several hundred of which are set aside for people most in need. Librarians in Seattle partner with local community groups to lend them directly to those experiencing homelessness and those living in the city’s “tiny home” villages. Since the pandemic, they’ve increased the number of devices for people in need from 250 to 325. All are available to borrow for several months at a time and are often paired with training sessions from library staff, said Andrew Harbison, assistant director of Collections and Access at Seattle Public Library.

We’ve long known at the library how hard it is to be at the wrong end of the digital divide.

Linda Johnson, CEO of Brooklyn Public Library

Hahn, the Cherokee Library director, says he would love to lend out Wi-Fi hotspots in addition to the few Chromebooks his library has but thinks community need is so vast that any program he started with current resources would be quickly overwhelmed. The local public high school let students bring laptops home to use for their (voluntary) remote-learning program, but not hotspots, he said.

Several librarians independently said that their hotspot-lending programs are “just a drop in the bucket” or “just a Band-Aid” to the overwhelming need for reliable internet and the basic skills to use it.

“Even to work at McDonald’s, you’ll get a 30-page online application, and if you’re not comfortable with a drop-down menu, this is really going to be a challenge,” said Kate Eppler, manager of The Bridge at Main, a literacy and learning center in the San Francisco Public Library system. “Digital literacy is a lot like print literacy—it’s something you can get comfortable with, but it takes practice and can take a lot of help.”

Eppler and her colleagues are still working behind closed doors, answering people’s questions through the main phone line since the library remains closed. She also regularly refers people to the nonprofit Community Tech Network’s Home Connect program, which provides free computers and lessons to seniors in the area, and the Tenderloin Technology Lab, a free computer lab that has moved outdoors (with plastic gloves and social distancing) since the coronavirus crisis began.

“We have a lot of folks trying to get online to access their stimulus checks—people who maybe don’t have a permanent address to have their checks sent to them and have been unable to access the money they should be receiving,” said Amanda Brown, the Tenderloin Technology Lab’s manager.

Libraries have been providing other resources since the shutdown as well. Many have started curbside book pickups. They’re doing Facebook Live story hours for kids or reading books over the radio. They’re printing out paper applications for unemployment benefits, then collecting and mailing them. In Cherokee, Hahn has been putting books and art supplies into the free lunch bags that the public schools are distributing this summer. Some librarians are even using their libraries’ 3D printers to make plastic face shields, and sewing machines to make fabric masks.

Librarians also expect demand to grow as shutdowns end, especially for the job seeker programs many of them run.

“We know that in times of recession, like during the last one, that demand for workforce related services skyrocketed,” said the ALA’s Visser. “So now, thinking about all of the people who have lost jobs or businesses that have closed.… We know that that is going to be a number one thing that people are going to be doing when libraries are reopening.”

But the recession also has local government budgets shrinking and private donations taking a hit—things libraries depend on. When the Public Library Association’s survey in March asked about library staff’s greatest needs, funding and increased job-search-related services post-pandemic were among the most common responses.

The CARES Act did provide for stimulus funds to local libraries, $30 million of which has already gone to the states to expand local libraries’ digital access programs. According to Visser, the ALA is pushing Congress for $2 billion more.

Money isn’t the only consideration: Brooklyn Public Library’s Johnson pointed out that in the city, space is at a premium. As they plan how libraries will reopen, she said, librarians are currently discussing taking out every other computer in each lab to create more distance between patrons.

“Never before did people need access more—in a day and age where the government is requiring more and more to happen online—than during a pandemic,” said Johnson. “It is a true perfect storm: The deprivation is more extreme than ever, and the need is higher.”