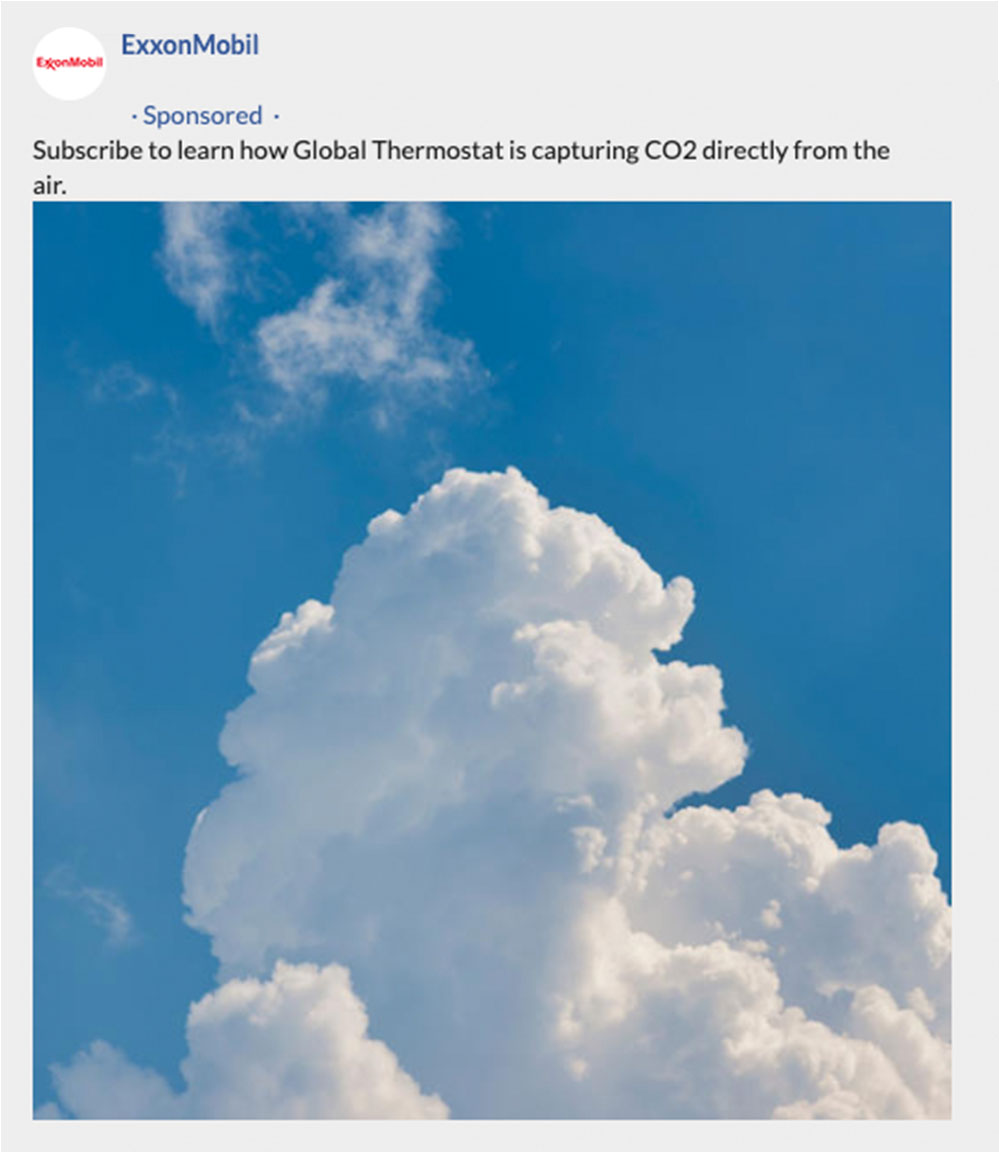

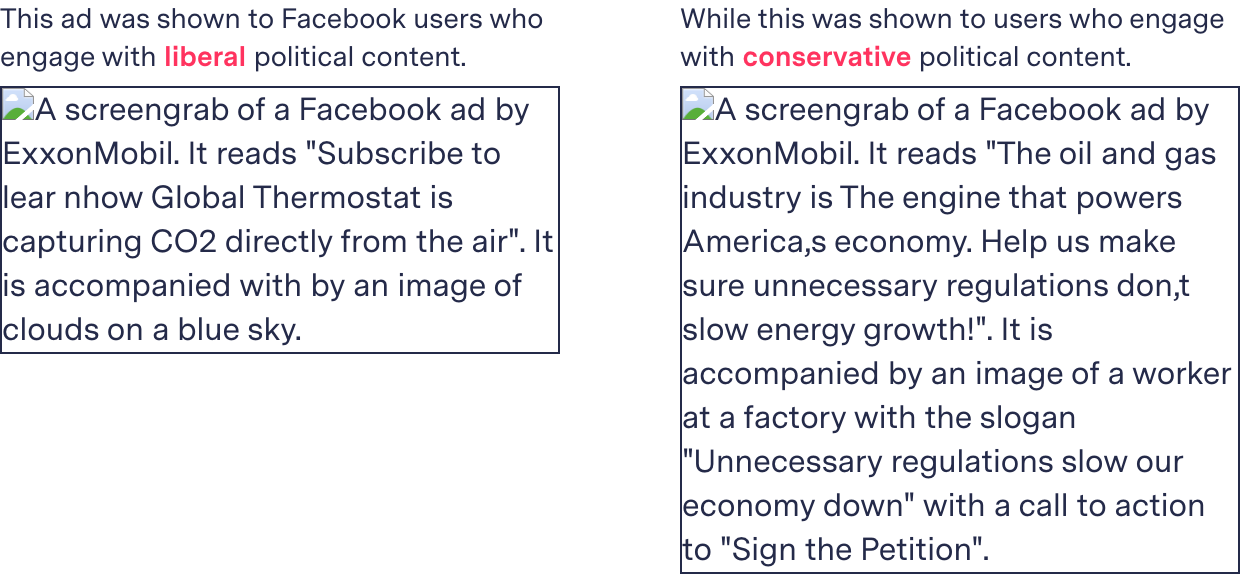

Liberals on Facebook are given one picture of ExxonMobil. To them, the multibillion-dollar oil giant sells itself as turning over a new leaf, exploring “carbon capture” techniques that put carbon back into the ground.

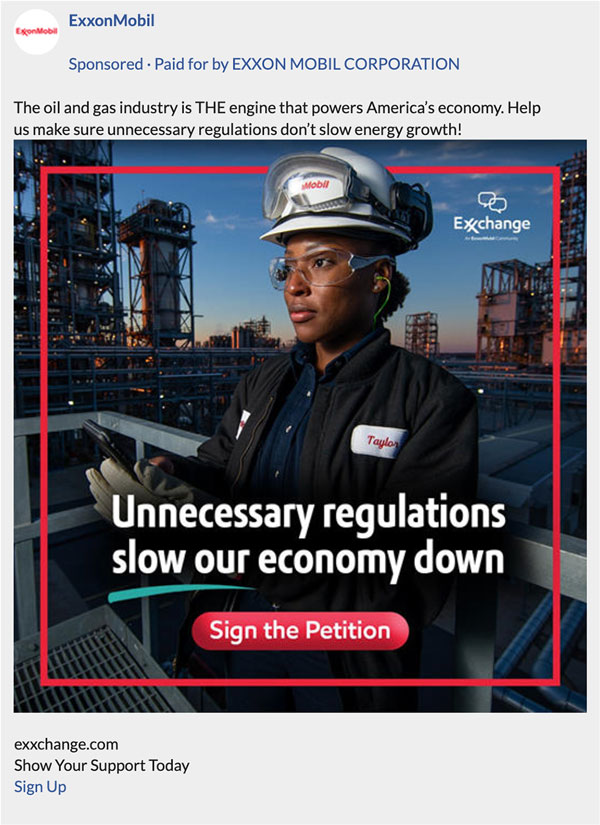

If you’re a conservative, Exxon has a very different message: “The oil and gas industry is THE engine that powers America’s economy,” reads one ad targeted at conservatives. “Help us make sure unnecessary regulations don’t slow energy growth.”

This ad was shown to Facebook users who engage with liberal political content.

While this was shown to users who engage with conservative political content.

The Markup found 18 Exxon ads on Facebook targeted to political liberals and 15 to conservatives—many with messages implying a contradictory attitude toward the urgency of adapting to climate change. The ads—and information about their targeting—came from the Ad Observatory at NYU’s Cybersecurity for Democracy project.

Exxon is one of a handful of companies The Markup found targeting specific, and sometimes conflicting, Facebook ads to people of different political beliefs. Facebook offers a wide array of options for advertisers looking to hit specific groups of people with their messages—from things like “Engaged shopper” to “Friends of Soccer fans”—including several political options like “Likely engagement with US political content (conservative)” and people interested in “Democratic Party (United States).”

ExxonMobil did not respond to several requests for comment.

Much has been made of America’s seemingly growing political polarization, with some commentators blaming Facebook’s algorithmic push to encourage people to join groups that sometimes contain highly partisan, vitriolic content. But whatever the cause, experts say brands’ decisions to appeal to people because of their political leanings indicates that they’re using Facebook’s ad targeting system to take advantage of that polarization.

“As parties have become more sorted and distant from one another,” said Bridget Barrett, a Ph.D. student who researches political communication at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, “political parties may become a market segment in their own right.”

As parties have become more sorted and distant from one another, political parties may become a market segment in their own right.

Bridget Barrett, UNC Chapel Hill

Facebook didn’t respond to a question about Exxon’s use of its ad targeting tools.

Facebook does not share information about how ads are targeted with the general public and only shares spending information about “social issue, electoral or political” ads. The Markup analyzed data from June 2020 through March 2021 from the Ad Observer browser extension of NYU’s Cybersecurity for Democracy project, which enables volunteer participants to contribute the ads they’re shown and what Facebook discloses to them through the “Why am I seeing this ad?” feature. Because Facebook doesn’t disclose all the targeting choices to anyone, it’s possible that the ads in this story were targeted to other political groupings as well.

Other Exxon ads targeted at liberals said the company helped mass-produce a new N95 mask design and trumpeted how “Modern energy can transform lives.” Conservatives, on the other hand, were shown ads about how pipelines are essential infrastructure that keep oil- and gas-based energy affordable.

Though the ads were targeted at people based on their politics, Facebook did not consider the bulk of the ads to be political so did not disclose how much Exxon had spent on them. Exxon did tally $7 million in “political” ads in the six months leading up to the November 2020 election, according to Facebook Ad Library data—comparable to the $8.7 million Exxon spent lobbying Congress in 2020.

When The Markup approached Facebook, the company said that some of the ads The Markup identified for this story should have been labeled political and removed them from the platform because the advertiser failed to comply with Facebook’s rules for labeling political ads. Facebook declined to answer any of our other questions, including which of the ads were removed.

Comcast, the cable and internet service giant, also runs Facebook ads about its good works. Ads about providing internet access for low-income kids to do their remote schoolwork are targeted just at liberals. The company has also run ads targeted just at conservatives, claiming it’s the “#1 employer of veterans.”

Lee McGuigan, a media studies professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, said Exxon and the cable company share a basic goal with these ads: improving a not-so-great public image.

“Comcast is also in a delicate political spot, not only based on the possibility of regulation, but also because of partisan public opinion,” McGuigan said. “Cable is a well-hated industry, all around, of course.” He said liberals often dislike Comcast for its perceived monopolism, and conservatives may dislike Comcast’s MSNBC television channel.

Comcast didn’t respond to requests for comment.

The Markup found ads bought by Comcast, multinational gold mining conglomerate Barrick, and pharmaceutical industry lobbying group PhRMA targeting Facebook users of both political leanings with different messages.

Numerous consumer products companies target one side of the political spectrum. Ads for Nike’s lines of sneakers honoring LGBTQIA+ people and Native American and Indigenous Heritage were targeted specifically to people interested in the Democratic Party. Credo Mobile cellphone company and Ben & Jerry’s ice cream both target political liberals.

Ben & Jerry’s, which advertised a voting rights rally (with free ice cream) and a reminder to vote in Georgia’s Senate runoff this past January to liberals, said in a written statement that it “does purchase political ads to build and target audiences based on political data in order to advance its activism and advocacy campaigns and provide ways for people to action.”

Black Rifle Coffee, which sells military-themed coffee, targeted Facebook ads at people interested in the Republican Party or Donald Trump. MyPillow, a bedding company that also advertises on Fox News and is run by prominent Trump supporter Mike Lindell, targets some of its Facebook ads at conservatives.

None of the companies other than Ben & Jerry’s responded to The Markup’s requests for comment.

With Exxon’s ads, “They’re clamoring for what’s known as social license,” said Kert Davies, director of Climate Investigations Center, the idea that the “oil industry is good for the economy, good for jobs,” with the subtext of “don’t do anything that hurts the oil industry.”

Ad targeting is certainly not a new tactic. For instance, decades ago, before merging with Exxon, Mobil bought space to promote its views on The New York Times’ op-ed page, which Mobil claimed affected the Times’ editorial stance, and sponsored Masterpiece Theatre, a public television program popular with “opinion leaders,” who in turn, Mobil claimed, “molded general public opinion.”

Robert Brulle, a professor at Brown University, said segmenting audiences for ads like this is “pretty much a standard practice” with data, albeit less precise, about the demographics of who watches which TV shows.

“There are focus groups to test what they’re doing. This works with this population and this works with that population,” Brulle said.

But the targeting capabilities offered by Facebook allow a much broader array of data-driven advertising.

Exxon also targets at least 13 of its ads to lists of people that it uploads to Facebook based on data from LiveRamp, a data broker that helps companies figure out how to use data to target specific people across multiple platforms, according to data from The Markup’s Citizen Browser project, which collects news feed data from a panel of users across the United States.

In the middle of the 2010s, as microtargeted political advertising came to public attention, there was concern that politicians would use ads to make conflicting promises or express incompatible viewpoints to different people. Political candidates often segment their audience, talking about crime to married women and Social Security to older voters, but few examples have surfaced, in the context of elections, of politicians making contradictory promises with microtargeted ads. In fact, relatively few political advertisers (mostly ballot propositions and industry trade groups) are even talking to partisans from both sides.

One such example is “All Voters Vote,” the proponents of a Florida constitutional amendment to let all voters vote in party primaries, not just registered party members, as is the current rule. The difference in how the ads, found in NYU’s Ad Observer, described who would get an expanded say was subtle: Liberals got “every voter,” and conservatives, “every American taxpayer.”

Overall, however, as consumer tastes appear to grow apart, following their political views, “most companies don’t politically bifurcate their messaging,” said Barrett. The reason, she said, “is pretty simple: Good, consistent branding is hard enough to do for one audience.”