Introduction

Since the Israel–Hamas war began, hundreds of users have accused Instagram of censoring their posts supporting Palestine. Many users specifically said that what they were sharing on Instagram was being shadowbanned—that is, hidden for everyone except the original user who posted. To investigate, The Markup reviewed hundreds of screenshots and videos from users, analyzed metadata from thousands of accounts and posts, spoke with experts, and interviewed 20 users who believed their content had been blocked or demoted.

While there was no universal understanding among users we interviewed as to what it meant to be shadowbanned, they reported a wide variety of behaviors that could be a form of censorship, such as disappearing comments, broken links, and dips in how many people saw their videos.

We attempted to programmatically investigate these examples—but because Meta limits people from testing Instagram at scale, we instead scraped publicly available data and manually simulated user behavior with nearly 100 accounts.

Our investigation found that Instagram heavily demoted nongraphic images of war, deleted captions and hid comments without notification, suppressed hashtags, and limited users’ ability to appeal moderation decisions.

Data Collection

Our investigation collected structured data from instagram.com and anecdotal data self-reported by Instagram users. We also created our own dataset after conducting a series of experiments on Instagram.

Instagram Profile Data

To investigate what people were experiencing on Instagram, The Markup tracked, decoded, and documented some of the data that Instagram receives from Meta’s servers. We started an internal data dictionary and learned from a dictionary Matteo Di Cristofaro created for his book on processing social media data.

We chose dozens of Instagram accounts to examine: news organizations (including Al Jazeera, CNN, The Times of Israel, the BBC), Palestinian journalists reporting from Gaza, individuals and organizations who’d complained publicly of being shadowbanned, and a “control” group of the first 20 follows recommended by Instagram when we created a new account.

We took regular snapshots of the profile page data for each of those accounts over days and weeks and compared them over time and to each other, looking for any changes or differences that might shed light on the experiences people were describing.

We found some interesting nuggets: One parameter named is_regulated_c18 controls whether a news organization’s account is blocked from view in Canada, and another parameter called should_have_sharing_friction when set to true causes an “Are you sure?” dialog box to pop up when you try to share content posted by that account. If another parameter named media_overlay_info is defined, the post will be blurred and a warning message displayed; this is how users are given the choice of whether they’d like to see content that Instagram has marked as disturbing.

Although this deep dive into profile data was interesting, it didn’t uncover anything that explained the struggles Instagram users had been reporting. See Limitations: Lack of Available Data on Instagram for more details.

Instagram Reels View Data

Many users, when describing their experience being shadowbanned, pointed to sudden unexplained dips in engagement numbers, especially in the number of people their Stories were reaching. Some users shared screenshots showing a drop from hundreds of thousands of engagements down to thousands or even hundreds.

Instagram users can see the engagement numbers on their Stories if they have business or creator accounts through a feature called “account insights,” but those numbers aren’t visible to the public. One aspect of engagement data on Reels is public, however: A number in the lower-left corner shows how many times that particular Reel has been played.

Although most users we spoke with did not post Reels regularly, and only one suspected that their Reels engagement had dropped due to shadowbanning, we hypothesized that an artificial dip in engagement might be mirrored in Reels traffic.

The Markup collected and charted historical view numbers on Reels from a handful of accounts stating they had been shadowbanned to see whether their reach had changed significantly after Oct. 7, 2023. We noticed some wild fluctuations in play counts over time but nothing to conclusively show a pattern of suppression.

Anecdotal Data from Users

The Markup spoke with 20 Instagram users and collected hundreds of screenshots that showed reduced reach, confusing moderation decisions, unexplained errors, and other strange phenomena affecting accounts.

The Instagram users we interviewed were a mix of people who responded to a callout on The Markup’s Instagram page and users we reached out to who had publicly said they’d been shadowbanned. Four sources were journalists and 13 had professional creator accounts. We spoke to users with a wide range of followers: One source had more than 1 million followers, two had more than 300,000 followers, five had more than 10,000, seven had more than 1,000, while the remaining sources had fewer than 1,000 followers.

Although these users’ experiences were varied, we identified a handful of distinct threads:

- When Instagram removed content that our sources posted about the Israel–Hamas war, users were not always shown the option to appeal the decision.

- Instagram deleted content for violating a specific guideline, but the content did not appear to violate said guideline.

- Accounts experienced drops in reach or engagement without any notification that the visibility of their content might have been affected.

Markup Experiments

Using the three common experiences Instagram users described to us, we designed a series of experiments to re-create those scenarios, as well as variations on those scenarios we wanted to test.

Experiment Setup

Early Trials

The Markup performed an early set of trial experiments to determine what was possible to test for at a small scale. We used a mix of 18 personal and test accounts over the course of several weeks to post, like, comment, and report. We recorded and analyzed the data, and our results were promising, but there was enough variation that we decided to design and execute a more rigorous set of experiments with a larger pool of testers.

Full Trials

The Markup created 70 accounts that we used to run experiments in early February 2024. We grouped the accounts into the following categories to carry out the experiments we’d designed:

- 10 accounts that took no action that could be interpreted as violating community guidelines. These were our control accounts.

- 10 accounts that posted comments that looked like commercial spam

- 10 accounts that posted comments that looked like bullying or harassment

- 10 accounts that posted content using banned hashtags, a type of restricted hashtag that returns no results upon search

- 10 accounts that replicated comments related to the Israel–Hamas war that Instagram had already classified as spam for other users; we later used these accounts to repost other users’ content about the Israel–Hamas war.

- 10 accounts that followed, among others, official Israeli government accounts, news sources based in Israel, news aggregators posting content that highlighted the stories of Israelis involved in the conflict, and advocates for the return of Israeli hostages.

- 10 accounts that followed Palestinian journalists reporting from Gaza, news aggregators posting content that highlights the stories of Palestinians involved in the conflict, and ceasefire advocates, among others. One account was suspended before it could fully participate in the experiment for this group, so we replaced it with an “early trial” account during the experiments. See Limitations: Brand-New Instagram Accounts for more details.

We used these new accounts to follow recommended accounts, like posts, amplify posts, or leave comments to imitate the behavior of a typical user. We created and accessed all of these accounts manually, but we did not take any measures to guarantee that the accounts could not be associated with each other. See Limitations: Account Association for more details.

We also used 14 existing accounts to make hashtag observations and “like” posts.

Our small-scale testing did not allow us to isolate each experiment, and we did not use any statistical significance methods, like chi-squared tests, which require that the data meet assumptions of independence. Because of the experiments’ limitations, we did not treat observations as independent of one another. See Limitations for more details.

Experiment: Hashtag Suppression

Background

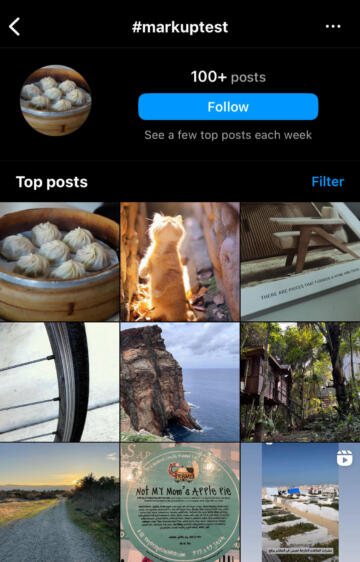

On Instagram, every active hashtag has a page where users can scroll through a subset of posts with that hashtag. For example, the page for #axolotl features pictures and artwork of that particularly lovable salamander.

Not every hashtagged photo will necessarily show up on that hashtag’s page. For a new hashtag, we had expected all its tagged posts to appear. But we learned in early trials that this wasn’t the case. For a popular tag like #rabbit with more than 19 million photos, you can scroll through images until your thumb cramps. But a hashtag with a couple dozen posts will sometimes display only a handful of photos at once.

If you’re looking at tagged photos on the Instagram mobile app, you’ll see that you can choose to filter by either “Top posts” or “Recent top posts,” suggesting that if a post is not already popular, it won’t be displayed. (Instagram quietly removed the option to view “Recent posts” sometime in 2023, though it’s been testing it on and off since at least 2020.)

Instagram lists a few different factors that affect a post’s inclusion or order within a hashtag, but our hypothesis in designing experiments using hashtags was that a user’s post would be less likely to show up as a “top post” on a hashtag page if Instagram had flagged the account or its content, and that we could use this as a proxy for shadowbanning.

Setup and Baseline Testing

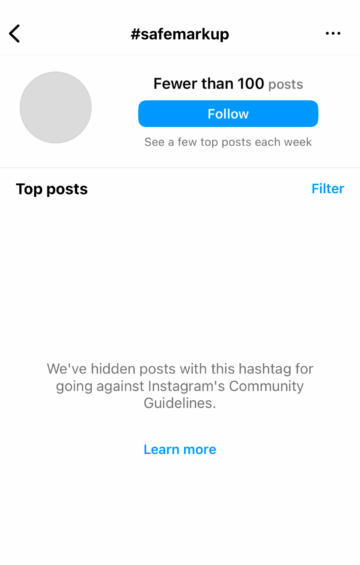

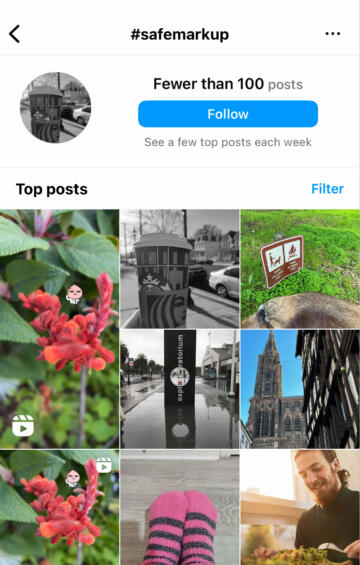

To create an environment free from the influence of accounts that we didn’t control, we made two new hashtags: #safemarkup and #markuptest. We used #safemarkup as a control hashtag. We only posted unremarkable content to that hashtag, from accounts that were not slated to trigger violations but would be reported for violations later. We used #markuptest to run a series of experiments designed to figure out what actions an account could take (or be reported for taking) that would result in its posts reliably not appearing on the hashtag’s page.

Our 70 experiment accounts followed top users recommended by Instagram, then posted everyday life photos like pets, plants, and the occasional meme into #markuptest and #safemarkup. As expected, a post using either hashtag did not always automatically populate onto the corresponding hashtag’s page.

The first day of testing, all 10 posts uploaded with #safemarkup were visible on the hashtag’s page, but only 56 of the 60 posts tagged with #markuptest were visible on its hashtag page. Over the course of our three-week experiment, 148 of 152 “everyday” photos appeared at least once on #markuptest. We checked both hashtags from different accounts multiple times throughout our experiment and recorded the posts that appeared.

These baseline tests told us not to expect every post to be visible on a hashtag’s page, but that we could expect most to show up at some point. A deviation from this baseline may imply that an account’s actions affected the visibility of its content.

Instagram Deleted Captions Using Our Hashtag

In our testing, we observed dozens of times, but not every time, that when an account shared a photo with #markuptest in the caption, the photo was posted to the account’s feed successfully, but the entire caption had been deleted. Instagram did not notify any of our accounts that the text of our posts had been altered.

In one instance, an account was told “there was an error saving your changes” when trying to share a post with #markuptest. When the hashtag was removed, the post uploaded successfully.

As a workaround, we edited photo captions to include the hashtag after photos were posted, which allowed the photos to appear on the hashtag’s page.

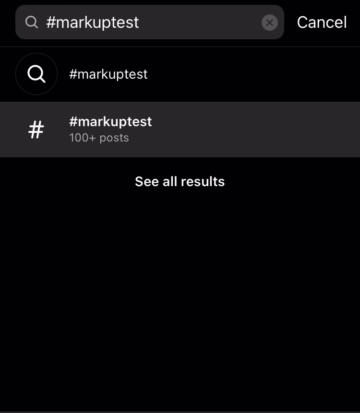

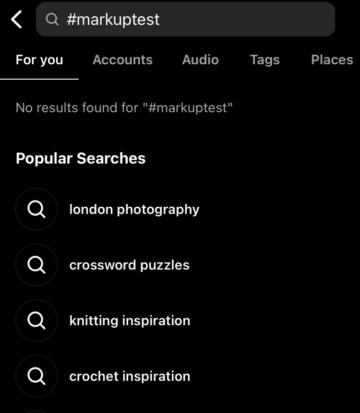

Instagram Suppressed Hashtags

We observed that sometimes, users were met with an error when they tried to navigate to the #markuptest page. The #markuptest hashtag would show up in search, along with a description like “100+ posts” indicating how many times it had been used, but selecting the hashtag took users to a new screen that said “No results found for #markuptest.” Similarly, if the user selected #markuptest in the caption of a post, which typically acts as a link to the hashtag page, they would be met with the same error. Other accounts were able to find and browse #markuptest without issue.

Experiment: Accounts with a History of Advocacy

The Markup used 20 accounts to test whether clear advocacy in the conflict affected how Instagram moderated content.

On the first day of testing, each of these accounts followed top accounts suggested by Instagram and posted to #markuptest. All of their #markuptest posts were visible on the hashtag page before they interacted with and posted about the war. The next day, one account was suspended; at this point, none of these accounts had interacted with any accounts covering the conflict.

Ten accounts followed, among others, official Israeli government accounts, news sources based in Israel, news aggregators posting content that highlighted the stories of Israelis involved in the conflict, and advocates for the return of Israeli hostages. Nine more accounts followed Palestinian journalists reporting from Gaza, news aggregators posting content that highlights the stories of Palestinians involved in the conflict, and ceasefire advocates, among others. The accounts liked and reposted content from those they had followed, and posted content with hashtags that reflected their ideological categorization.

No Evidence of Shadowbanning Based on Ideology

Using public domain photos from Wikimedia Commons, the accounts made posts of peaceful demonstrations with the hashtag #freepalestine or #istandwithisrael, depending on their ideological assignment. They then posted more everyday photos to #markuptest.

There was no significant discrepancy between the visibility of posts from our accounts before and after they engaged with and posted political content, and none between the visibility of Israel and Palestine accounts.

Following and reposting political content and making ideologically aligned posts did not appear to affect the visibility of the accounts’ subsequent posts on #markuptest. All of the “everyday” posts from Israel and Palestine accounts had been visible at least once on the #markuptest page by the end of our experiment.

It’s important to keep in mind that our test accounts cannot statistically represent the millions of people who use Instagram to post about the Israel–Hamas war. Therefore, while we did not find any clear evidence of shadowbanning based on an account’s advocacy history, our results cannot be extrapolated to say that there is no difference in visibility between accounts aligned with Israel or Palestine. See Limitations: Brand-New Instagram Accounts for more information.

Instagram Suppressed Photos of War

Two days later, we also used these accounts to test whether war imagery was more likely to be shadowbanned than other kinds of posts. The 19 test accounts posted photos from the war and used the hashtag #markuptest. The posts were images released into the public domain by the Israeli Defense Forces Spokesperson’s Unit (and one photo preceding the Israel–Hamas war was originally posted to Flickr) and included subjects like tanks, soldiers, guns, and buildings destroyed by bombs.

Instagram’s community guidelines say that the platform “may remove videos of intense, graphic violence to make sure Instagram stays appropriate for everyone.” The company also said that it will not recommend “content that may depict violence, such as people fighting.” The photos we posted did not contain images of casualties, blood, acts of violence, or people in distress.

The Markup found that nongraphic photos depicting the war were 8.5 times more likely than other posts to be hidden from #markuptest. In the first week of the experiment, only six of 19 war posts ever appeared, and usually no more than two to six were visible per observation day. In contrast, 36 out of 38 other posts from the same accounts appeared in #markuptest at least once.

By the end of two rounds of testing, only nine of 29 war photos were ever visible, while 158 of 172 other posts were visible at least once on #markuptest. This discrepancy in visibility between war photos and other photos, along with the consistency in the lack of visibility among war photos, implies that Instagram may routinely suppress posts containing war imagery.

None of the test accounts were notified that Instagram had restricted the visibility of their posts.

No Evidence of Shadowbanning Based on Erroneous Community Reports

Two days after posting the first set of war photos, we used test accounts to report each post at least twice for violating Instagram guidelines on dangerous organizations and individuals, even though none of the photos violated the DOI policy. Before these posts were reported, two of 19 war photos were visible on the #markuptest page. After the reports were submitted, four were visible on the #markuptest page. So the number of war photos visible after reporting actually increased, although it should be noted that very few of them were visible in the first place.

Experiment: Spam vs. Bullying Violations, and Whether Users Can Appeal

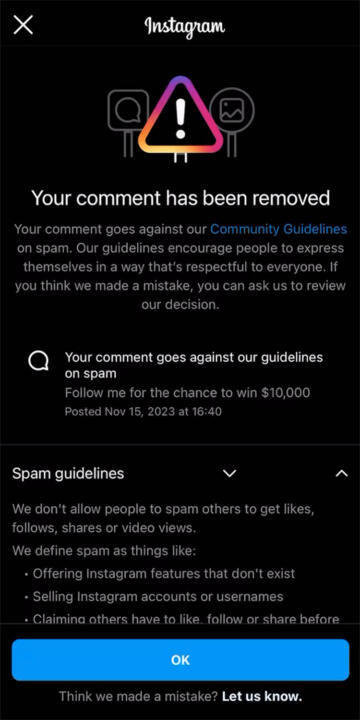

The Markup heard from several Instagram users whose comments supporting Palestinians or criticizing Israel’s actions in the war were deleted by Instagram for being spam. In the notice of removal, Instagram defined spam for these users as:

- Offering Instagram features that don’t exist

- Selling Instagram accounts or usernames

- Claiming others have to like, follow, or share before they can see something

- Sharing links that are harmful or don’t lead to the promised destination

Users whose comments were removed were baffled since their comments did none of these things.

In a community guidelines FAQ, Instagram offers a different, sweeping definition of spam as forms of “harassing communications.” The critical comments we collected from our sources could perhaps fit into this definition of spam, but Instagram also removes content for “bullying and harassment,” defined as “unwanted malicious contact.” It is unclear how Instagram distinguishes the two categories.

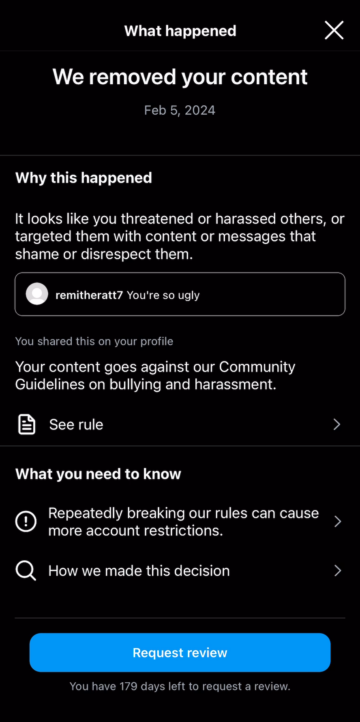

In early experiment trials, we noticed a pattern: When Instagram deleted a comment and labeled it “bullying and harassment,” users were given the option to request a review—but when comments were deleted as “spam,” users were not. Instagram explains that, for certain types of content, users can’t request a review of its removal, but it does not elaborate on which types of content these are.

To investigate this further, The Markup created accounts that intentionally posted comments with the expectation that Instagram would remove them. We used Meta’s definition of spam and bullying and harassment to design the comments.

Comments designed to trigger a spam violation:

- “Follow me for the chance to win $10,000!”

- “Like this comment to get more followers”

- “DM me to get a discount code at Amazon”

- “Message me to learn how to get a dislike button!”

- “My account is for sale, message me if you’re interested in buying it!”

Comments designed to trigger a bullying and harassment violation:

- “You’re so ugly”

- “I hate you”

- “You're disgusting”

- “You’re so stupid”

- “You’re a disease”

The comments were posted on other test accounts we created. Using these accounts, we looked into the deletion or visibility of the comments, when users were able to request a review, and the overall visibility of accounts that had their comments suppressed, as outlined below.

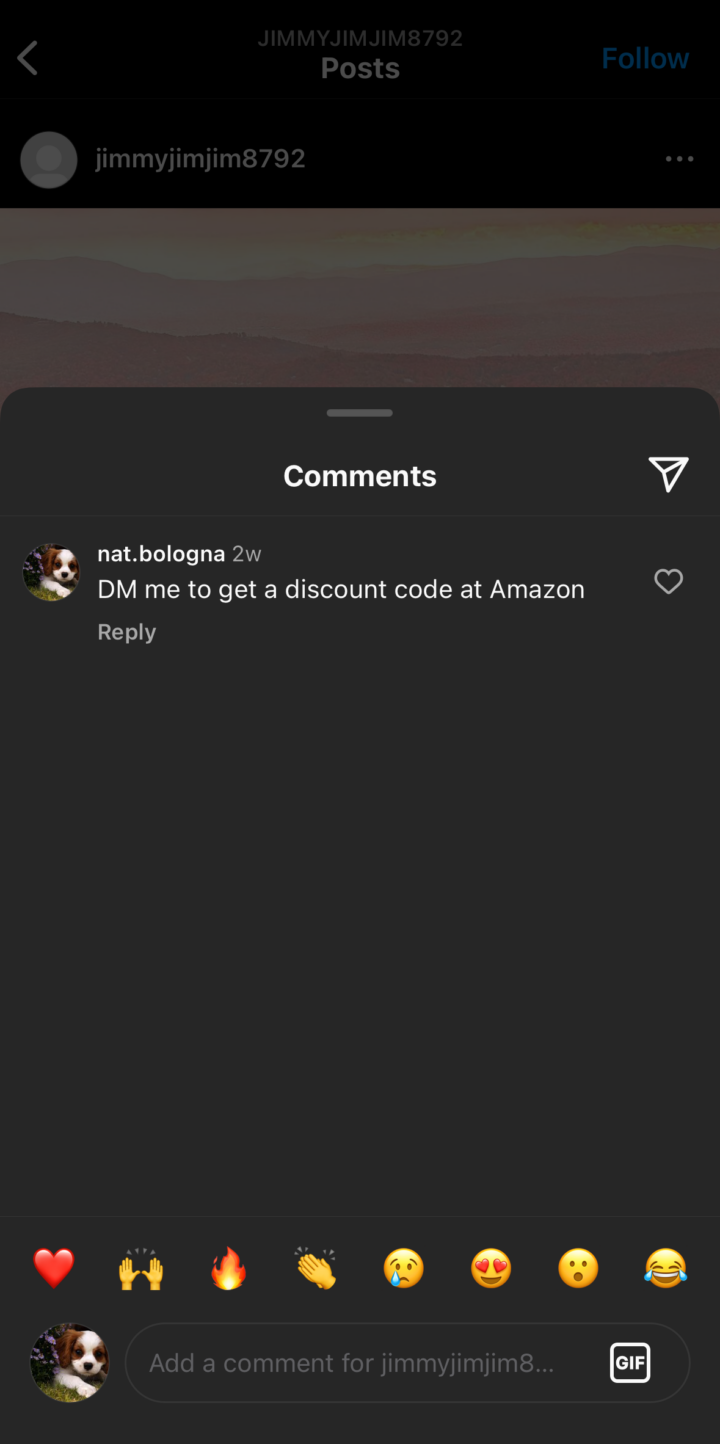

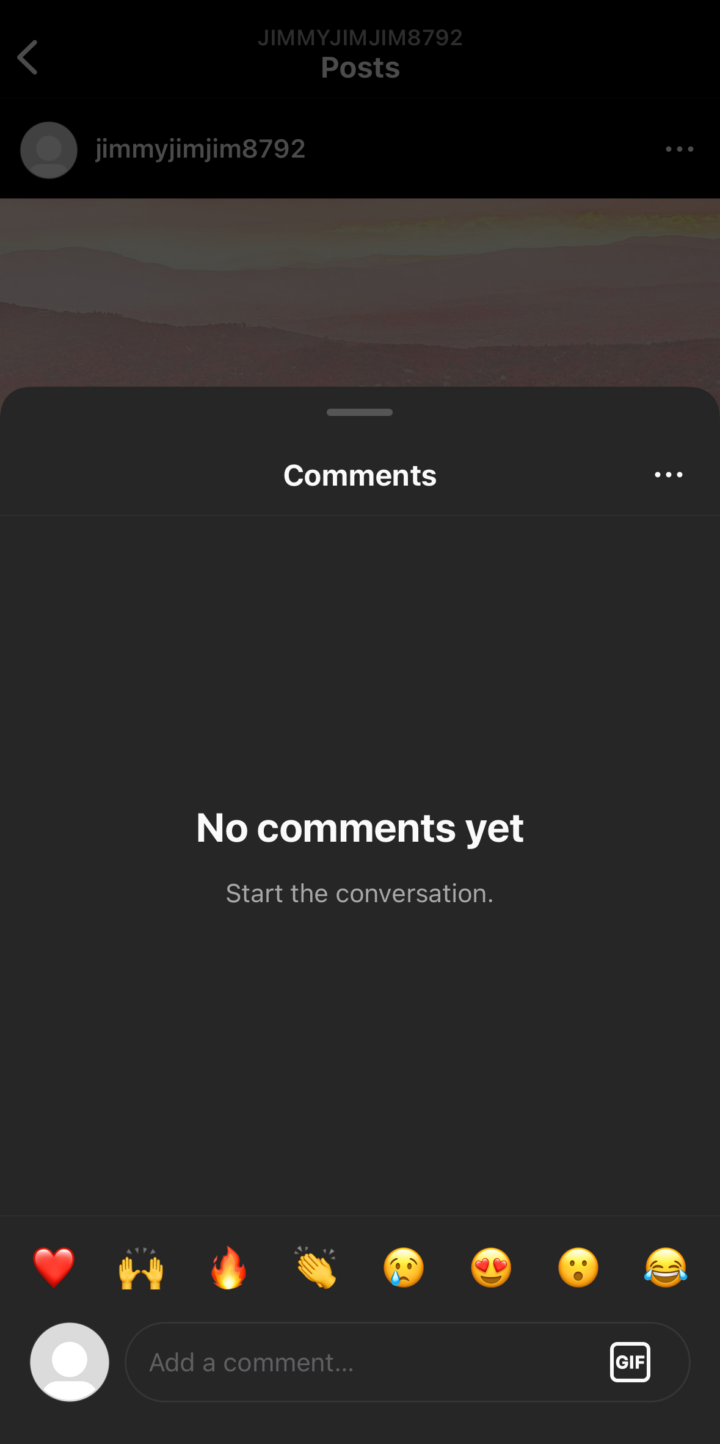

Instagram Shadowbanned Comments

In early trials, some of our comments disappeared with no notification from Instagram that they had been removed. The user who posted the comment could still see it, but it was not visible to any other Instagram users, even under the “View hidden comments” section.

In the February experiments, we monitored the comments posted by our test accounts and saw that they were repeatedly shadowbanned by Instagram.

Eight of the 10 spam comments we posted were always visible to the commenter but never visible to other accounts. The commenters received no notification that their comments had been affected. The two spam comments that were visible to users other than the commenter both read “Message me to learn how to get a dislike button.” (Eight days later, one of those accounts was suspended, although it had not behaved any differently than other accounts.)

-

A post shows “View 1 comment” for all users -

The comments section, viewed from spam test account -

The comments section, viewed from all other accounts

We observed the same behavior with two bullying comments. One account, which posted “You’re so stupid,” was suspended; another that posted the same comment was not, but the comment was hidden for other users. “You’re disgusting” also did not appear for other users, but another instance of the comment was placed in a “View hidden comments” section. “You’re a disease” was twice placed behind the hidden comments section.

We also checked the visibility of comments from a desktop web browser that was not logged into an Instagram account. Interestingly, we could see the spam comments that were hidden from all logged-in users except the commenter, but we could not see any of the bullying comments. The vast majority of Instagram users, however, likely do not access the platform from a web browser that is not logged into an account. This does not change the fact that the comments would have been invisible to all users accessing the platform in a typical way.

“Request review”

Since Instagram did not remove any of the spam comments posted by our test accounts and shadowbanned some of them, the platform did not send our accounts any notifications, including one for how to appeal. In contrast, two bullying comments that said “You’re so ugly” triggered a removal by Instagram for violating guidelines on bullying and harassment. The two accounts that posted this comment were given the option to request a review of the removal.

This is consistent with the results from our early trials in which two test accounts had comments removed as bullying and harassment and were both able to request a review of Instagram’s decision. When an account’s comment is relegated to the hidden comments section, users are not notified and are unable to request a review.

In early trials, Instagram removed the comment “Follow me for the chance to win $10,000!” for violating guidelines on spam after we posted it from a test account. This account was not given the option to request a review of Instagram’s removal decision. This is consistent with the accounts of three sources who had comments deleted by Instagram for violating guidelines on spam and were unable to request a review of the decision.

“Let us know”

Instagram’s notice of removal for spam shows users a message that says, “Think we made a mistake? Let us know.” The phrase “Let us know” is a link. Several users told The Markup that the “Let us know” link did not appear to function properly. According to one user, every time they used the link, the notification would “go away for a moment and then come back up,” in an endless loop.

The Markup’s testing also saw inconsistent responses. Sometimes after a user selected “Let us know,” Instagram confirmed that the feedback was submitted, while other times the prompt disappeared without any confirmation that feedback had been registered. There were no situations when selecting “Let us know” prompted the clear appeals process that “Request review” did in all cases.

Instagram’s help center has instructions for two ways that users can appeal a community guideline violation: through Account Status and through the Support Inbox. According to these instructions, the users will eventually be able to select a “Request a review” or “Request Review” button. There are no appeal instructions that include “Let us know.”

The Markup checked the Account Status and Support Inbox on multiple accounts that Instagram said violated community guidelines. For accounts that violated the dangerous organizations and individuals policy and were immediately offered a “Request review” option, we also saw the option under Account Status and Support Inbox.

For the one Markup “early trial” account that violated the spam policy, there was no option under Account Status or Support Inbox to request a review.

Experiment: Accounts with a History of Community Violations

Violating Instagram’s community guidelines can result in penalties like a disabled account, restricted access to certain features, and content removed or marked as ineligible for recommendation—meaning others won’t see your content in search results or the Reels feed and your account won’t be suggested as one to follow. Instagram said they also “filter certain words and phrases” to enforce community guidelines when users are commenting.

The Markup tested whether new posts from accounts that had previously violated community guidelines or posted content that Instagram would likely consider inappropriate affected the visibility of that account.

In early trials, we tested the visibility of one account that had two comments removed by Instagram, one for being spam and one for bullying and harassment, and another account that had one Story and one post removed, both for supporting dangerous organizations and individuals. We did not notice any visibility changes for those accounts after they received these community guidelines violations.

We expanded the scope of our experiment in the full February trials. We used 20 accounts to post comments designed to violate Instagram’s guidelines on spam and bullying (see Instagram Shadowbanned Comments), and then used those same accounts to post uncontroversial photos and videos before and after commenting to #markuptest.

No Evidence of Shadowbanning Based on History of Community Violations

Before the 20 accounts made spam and bullying comments, all but one of their #markuptest posts were visible. After they made their comments—most of which were shadowbanned or removed—the visibility of their #markuptest posts dropped temporarily, with 24 of 37 photos visible two days after their comments. We also observed the same temporary visibility drop on other accounts that did not participate in this experiment (54 visible posts out of 77).

However, by the end of our experiment, visibility rebounded, with 55 of 57 posts from spam and bullying accounts visible at least once. We could not account for the temporary hit in visibility to the hashtag.

No Conclusion on How Community Reports Affect Visibility

The Markup tested if multiple spam reports on a post affected the visibility of that post on our hashtag pages.

We used 10 accounts as controls that made random and uncontroversial posts to #safemarkup. None of our other accounts ever posted to #safemarkup. In the first six days, the safe accounts posted a total of 18 photos. Of those, three were never visible on the hashtag within the first week.

The day that we reported #safemarkup posts as violating guidelines on spam, 11 photos were visible on the hashtag. We reported those posts as spam twice using test accounts. We then “liked” each of the remaining seven photos twice using a mix of personal and test accounts to see if they were more likely than the reported posts to remain on the hashtag.

At first, these actions didn’t appear to matter. Two days later, out of 18 photos posted to #safemarkup, 16 were still visible and two were not, but those two posts had been visible the day before.

Nearly two weeks later, however, the hashtag was restricted. The feed of posts was replaced with an error message saying, “We’ve hidden posts with this hashtag for going against Instagram’s Community Guidelines.”

Eight hours later, the hashtag was once again showing posts.

By the end of our experiment, every post on #safemarkup had been visible at least once.

Instagram did not notify any of the accounts that posted to #safemarkup that their posts had violated community standards. Meanwhile, the day before the hashtag was temporarily restricted, 16 of 19 posts that our control accounts made in #markuptest were visible on that hashtag page.

Based on our experiments, we cannot draw any conclusions on whether community reports on spam affected the outcome of #safemarkup. The #safemarkup hashtag was restricted briefly, then appeared again; the accounts that posted in #safemarkup also appeared in #markuptest. We also do not know how many reports need to be made on a post in order for Instagram to trigger an internal review.

No Evidence of Shadowbanning Based on Use of Restricted Hashtags

Instagram says that it restricts a hashtag when people are using it in a way that consistently violates community guidelines. For example, when accessed via the Instagram app, the pages for innocuous-sounding but restricted hashtags like #elevator and #ice show a grid of thumbnails and a warning that recent posts for the hashtag are hidden.

Another category of restricted hashtags returns no results at all when you search for them; we categorize these hashtags as “banned.” In October 2023, the New York Times reported that Instagram had banned the #zionistigram hashtag from returning any search results. According to the Times, the hashtag had been used on posts that criticized Instagram for its alleged suppression of pro-Palestine content. #zionistigram was no longer banned during The Markup’s tests, so we used #dm, another banned hashtag.

We found this and other restricted and banned hashtags by searching the web for “Instagram banned hashtags,” which led us to several websites listing hashtags that have been censored, including #dm. A search for #dm yields no results in the Instagram app, while navigating to the #dm hashtag page on a desktop browser results in an error. Furthermore, in the Instagram app, selecting #dm in the caption of Markup test posts takes users to a page that says “Posts for #dm have been limited.” We used #dm in the experiments because the term is commonly considered harmless.

We tested whether using a banned hashtag would affect the visibility of subsequent posts made by an account. We used 10 accounts to upload inoffensive pictures and used the banned #dm hashtag in the caption. Each of these accounts then posted another photo using only the #markuptest hashtag.

In the baseline test, nine out of 10 photos tagged with #markuptest were visible on the hashtag’s page on the first day. Seven out of 10 photos posted directly after using the banned hashtag were also visible on the #markuptest page.

We then captioned photos with both #dm and #markuptest to test whether that would affect a post’s visibility on the #markuptest page. Later that day, four out of 10 photos showed up on the #markuptest page. We repeated this experiment two days later, and seven out of 10 posts appeared that day.

But by the end of our experiment, 39 out of 40 posts hashtagged by these accounts had appeared at least once on #markuptest, regardless of the additional banned hashtag. The one post that had never been visible on #markuptest page did not contain #dm in the caption.

It does not appear that using restricted hashtags or combining them with other hashtags makes a difference in visibility.

Limitations

Data Collection Timeline

Our data collection, analysis, and testing took place over the course of several months, from mid-October to mid-February. During that time, Instagram:

- increased the sensitivity of its “hostile speech” filter for comments originating from Israel and Palestinian territories, according to the Wall Street Journal;

- tightened its standards for what qualified as inappropriately graphic content for content originating in the region, which implies that accounts in different locations could post the exact same thing and experience different outcomes;

- announced that it had found and fixed bugs, changed defaults, and introduced new features;

- announced that it would allow “disturbing” imagery from Israel and Palestine if it were shared in a “news reporting or condemnation context” (according to the Oversight Board, Meta adjusted its policies in this regard “several times” and as early as 46 days before it was announced publicly); and

- refactored the format and content of some of the data being sent between its servers and the Instagram application.

Taken together, this means that a test or analysis done in late October 2023 may have produced different results than the same test or analysis performed in early February 2024.

Lack of Available Data on Instagram

Instagram’s public Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) are provided for developers who want to add features to their own applications, like publishing to or showing content from Instagram. There is no public API appropriate for data collection or analysis.

There are a few independent software libraries that allow users to access the communications between the Instagram web or mobile application and Meta’s back-end servers. This is the same data one can see by opening a browser’s developer tools while using Instagram and examining network traffic. We used one of these libraries and wrote scripts to access and analyze data, but we were frequently impeded by Instagram’s safeguards against data scraping. For example, accessing certain kinds of data required a logged-in account, and the one account we used was temporarily suspended. Our requests would also occasionally be rejected. This means that we were only able to collect and analyze data for a limited number of accounts over a short period of time.

Account Association

We didn’t take measures to guarantee that the test accounts could not be associated with each other. Each individual tester logged into multiple accounts from the same IP address, usually on the same devices. Instagram may have treated these associated accounts differently than if they’d each come from distinct IPs and devices.

Brand-New Instagram Accounts

Although we used our long-standing personal accounts to collect observations and file reports, all of the accounts we used to make posts and comments were brand-new. Instagram may consider the age of an account for the purposes of content moderation; the metadata for profiles contains the parameter is_joined_recently. This also means our experiments do not capture what would happen to real users with longer activity histories who have accumulated many more actions tracked by Instagram that could influence their accounts’ visibility.

Instagram also blocked some of our testers from creating accounts. This happened immediately to Markup staffers who used their work email addresses to sign up, as well as other testers using personal email addresses.

Two accounts were suspended the day after they were created. They both followed top users recommended by Instagram and posted everyday photos to their feed and #markuptest on the first day. One account had additionally posted uncontroversial Stories, written a positive comment on another user’s account, and tagged a photo with #safemarkup. We don’t know why these particular accounts were suspended; other accounts used by the same testers were not suspended.

Company Responses

Dani Lever, a spokesperson at Meta, Instagram’s parent company, responded to our questions with this statement: “Our policies are designed to give everyone a voice while at the same time keeping our platforms safe. We’re currently enforcing these policies during a fast-moving, highly polarized and intense conflict, which has led to an increase in content being reported to us. We readily acknowledge errors can be made but any implication that we deliberately and systemically suppress a particular voice is false.”

She also said, “Given the higher volumes of content being reported to us, we know content that doesn’t violate our policies may be removed in error.”

When asked about reports that users had unexplained drops in Stories viewed and accounts reached after they started posting about the Israel–Hamas war, even after Instagram’s bug fix was announced in October, Lever responded: “Instagram is not intentionally limiting people’s Stories reach. As we previously confirmed, there was a bug that affected people globally – not only those in Israel and Gaza – and that had nothing to with the subject matter of the content, which was fixed in October.”

Meta did not respond to our questions on differentiating between its spam and bullying policies. The company also did not respond to our question on how many spam appeals Instagram had received and approved since 2019.

Conclusion

We found that Instagram deleted captions using our hashtag, suppressed hashtags, suppressed nongraphic photos of war, shadowbanned comments, and denied users the option to appeal when the company removed their comments, including ones about Israel and Palestine, as “spam.”

We did not find evidence of Instagram shadowbanning an account based on its history of advocacy, erroneous user reports, history of community violations, or previous use of banned hashtags.

Correction, March 1, 2024

A screenshot of the #markuptest hashtag page was taken on Feb. 21, 2024. A previous version of this story misstated the year.