The Markup, now a part of CalMatters, uses investigative reporting, data analysis, and software engineering to challenge technology to serve the public good. Sign up for Klaxon, a newsletter that delivers our stories and tools directly to your inbox.

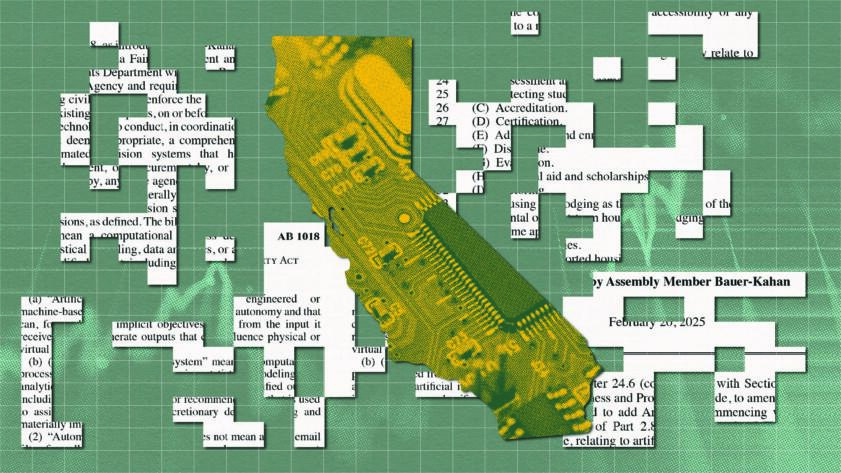

AI can get rid of racist restrictions in housing covenants and help people access government benefits, or it can deny people health care or a mortgage because of their race. That’s why, last month, for the third year in a row, Democratic Assemblymember Rebecca Bauer-Kahan of San Ramon proposed a bill to protect people from automated discrimination and AI that makes consequential decisions with the power to change a person’s life.

If passed, Assembly Bill 1018 will require the makers of AI to evaluate how the tech performs before it’s used and to notify people before AI makes decisions about employment, education, housing, health care, finance, criminal sentencing, and access to government services. It would also give people the right to opt-out of AI use and appeal a decision made by an AI model.

This year, California lawmakers like Bauer-Kahan are surging forward with 30 bills to regulate how AI impacts individuals and society, and some of the most high profile efforts are ones that the lawmakers attempted last year only to see them vetoed by Gov. Gavin Newsom or fail to pass.

In addition to the bill that guards against automated discrimination, lawmakers will again consider other legislation to protect society from AI, including a bill that requires a human driver in commercial vehicles and a new version of a measure to previously intended compel companies to better examine whether AI can cause harm.

The new wave of proposals follows a batch of more than 20 AI laws Newsom signed last year, but they are moving forward in a very different political environment.

Last year, the Biden administration supported measures to protect people from bias and discrimination and major companies signed pledges to responsibly develop AI, but today the White House under President Donald Trump opposes regulation and companies including Google are rolling back their own responsible AI rules. On his first day in office, Trump rescinded a Biden executive order intended to protect people and society from AI.

That dissonance could ultimately help the California lawmakers who want more AI protections. In a world of rapid-fire White House executive orders and chaotic, AI-driven decisionmaking by DOGE, there’s going to be more appetite for state lawmakers to regulate AI, said Stephen Aguilar, associate director of the Center for Generative AI and Society at the University of Southern California.

“I think California in particular is in position to say, ‘Okay we need mitigants in place now that folks are coming in with a wrecking ball,’” he said.

Bills will need to get through Newsom, who last year vetoed bills intended to protect people from self-driving trucks and weaponized robots and set standards for AI contracts signed by state agencies. Most notably, Newsom vetoed what was billed as the single-most comprehensive effort to regulate AI by compelling testing of AI models to determine whether they would likely lead to mass death, endanger public infrastructure, or enable severe cyberattacks.

Newsom vetoed the self-driving trucks and AI testing bills in part on the grounds that the bills could hinder innovation. He then created an AI working group to balance innovation with guardrails. That group should release recommendations about how to strike that balance in the coming weeks.

Democratic Sen. Scott Wiener of San Francisco, who carried the prominent AI bill, reintroduced a version of that proposal last month. Compared to last year, the bill is scaled back to protections for AI whistleblowers and establishment of a state cloud to enable research in the public interest. A former OpenAI employee who witnessed violation of internal safety policy told CalMatters that whistleblower protections are needed to keep society safe.

Bauer-Kahan was the first state lawmaker to propose legislation that contains the AI Bill of Rights, a set of principles that the Biden administration and tech justice researchers called foundational to protecting people’s rights in the age of AI including the right to live free from discrimination, the right to know when AI makes important decisions about your life, and the right to know when an automated system is being used. It didn’t become law, but roughly a dozen states have passed or are considering similar bills, according to Consumer Reports.

In a press conference to reintroduce her bill, Bauer-Kahan said the Trump administration’s stance on AI regulation changes “the dynamic for the states.”

“It is on us more,” she said, pointing to his repeal of an executive order influenced by the AI Bill of Rights and the stall of the AI Civil Rights Act in Congress.

The Tale of Two Administrations in Paris

Dueling perspectives on how the U.S and the rest of the world should regulate AI were on display earlier this month in Paris at a summit attended by CEOs and heads of state.

In comments at a private “working dinner” hosted by President Emmanuel Macron at the Elysee Palace, alongside people like OpenAI CEO Sam Altman and German Chancellor Olaf Scholz, AI Bill of Rights author and former director of the Office of Science and Technology Policy Alondra Nelson urged business and government leaders to discard misconceptions about AI like that its purpose is scale and efficiency. AI can accelerate growth, but its purpose is to serve humanity.

“It is not inevitable that AI will lead to great public benefits,” she said in remarks at the event. “We can create systems that expand opportunity rather than concentrate power. We can build technology that strengthens democracy rather than undermines it.”

By contrast, Vice President J.D. Vance at the same event said the United States will fight what he called excessive AI regulation. The U.S. refused to sign an international declaration to “ensure AI is open, inclusive, transparent, ethical, safe, secure, and trustworthy.”

The Trump administration’s position that regulation is a threat to AI innovation mirrors the talking points of major companies such as Google, Meta, and OpenAI that lobbied against regulation last year.

Debate about whether to regulate AI comes at a time when Elon Musk, President Trump, and a small group of technologists seek to build and use AI within numerous federal agencies to improve efficiency and save money.

By contrast, Vice President J.D. Vance at the same event said the United States will fight what he called excessive AI regulation.

Those efforts risk cutting benefits to people who depend on them. A report released in late 2024 by California-based nonprofit TechTonic Justice found that AI influences government services for tens of millions of low-income Americans, often cutting benefits they’re entitled to and making opportunities harder to access.

The majority of global venture capital investment and lots of talent and major companies are in the Bay Area, so California has more to gain or lose in regulatory debates than anywhere else in the world, said Matt Regan, a vice president for Bay Area Council, an advocacy group for more than 300 companies including tech giants Amazon, Apple, Google, Meta, and Microsoft. The Bay Area Council hasn’t taken a position on bills proposed in this session, but last year opposed Wiener’s AI testing proposal and the anti-discrimination bill proposed by Bauer-Kahan.

Regan said California regulators have proposed “over engineered protections and audits” that make the technology functionally useless and hamper businesses. The business group Chamber of Progress estimates that compliance with anti-discrimination bills in California, Colorado, and Virginia, could cost businesses hundreds of millions of dollars.

The political landscape has moved toward the center since California lawmakers proposed AI bills a year ago, which is why he thinks Assembly Speaker Robert Rivas urged his colleagues to focus on pocketbook issues. Due to those shifts, he thinks that in order for bills to avoid a veto like the kind that killed Wiener’s measure, Regan said lawmakers must draft bills that reach a “goldilocks zone,” balancing consumer protections with buy-in from business leaders. The forthcoming report from the working group convened by Gov. Newsom may offer tips on how to reach a goldilocks zone between making AI useful and punishing bad actors for abusing the technology.

Legislation with Teeth

A 2024 Carnegie California report found that a majority of Californians support an international agreement on AI standards as a way to protect human rights. But virtually every international agreement signed by tech companies is voluntary or has no legally-binding bite, said David Evan Harris in a presentation at an AI governance symposium held by UC Berkeley earlier this month.

That’s why he encourages civil society groups who want to make change to speak with California lawmakers. Harris is an advisor to the California Initiative for Technology and Democracy, a group that cosponsored laws to protect people from deepfakes that is getting challenged in court by Elon Musk’s company X, formerly Twitter. Previously he was part of responsible AI and civic integrity teams at Meta.

Last year he testified about AI 11 times in the California Legislature, and while he describes California as among the only places in the world where AI regulation is legally binding, he saw a frustrating pattern repeat itself: Lawmakers introduce AI bills, they get assigned to committees, and then “the bills get revised and completely rewritten by the tech companies.”

A prime example of this, he said, comes from a bill that attempted to fine social media companies for harming children. When it was introduced it had bipartisan support, but tech companies opposed the bill, and it got weakened then shelved in a committee hearing.

“The tech companies depend on nobody watching that happen,” he said.

Lili Gangas is chief technology community officer at the Kapor Center, a nonprofit organization based in Oakland that focuses on issues at the intersection of equity and technology, and follows policy developments in California and Congress. Given our current political environment and the elimination of AI protections by the White House, Gangas thinks there may be more support for passage of anti-discrimination bills in California and public support for such protections may be on the rise. Still, she worries that it may be difficult to pass AI regulation because of stepped-up lobbying in Sacramento by tech companies that set a record last year.

She also questions whether politicians with ambitions for higher office will put implementation ahead of drafting legislation that’s intended to bolster their careers. If lawmakers can overcome those challenges and keep costs low, she believes California can lead the way despite failures to do so by Congress and the Trump administration.

“I think that [rescinded executive order and failure to pass a law in Congress] makes it even more important now at the California level,” she said. “We can hold the line, center civil rights protections, and give the attorney general and individuals the opportunity to take action.”

States often pressure the federal government to protect people and their civil rights from emerging technology, said Alex Ault, policy counsel for the Lawyers Committee for Civil Rights Under Law. The racial justice nonprofit endorsed the Eliminating Bias in Algorithmic Systems Act in 2023 and AI Civil Rights Act in 2024 in Congress, two bills with similar principles to the Blueprint for an AI Bill of Rights and the anti-discrimination bill proposed in California.

A Carnegie California poll of 1,500 people released last fall named artificial intelligence one of six major issues facing Californians alongside climate change and infectious disease. Half of respondents said they’re worried or pessimistic about AI and 35% percent say they’re optimistic or excited.

“It would behoove state legislatures who are looking at what’s happening federally to say ‘Okay, what do we have control over?” Ault said. “How do we protect people’s rights?’”

Unlike Wiener, Bauer-Kahan did not water down her vision for AI regulation. As chair of the consumer privacy and protection committee, she’s one of the most powerful regulators of technology in the California Legislature, but last year the bill faced opposition by tech companies like Google, Meta, and OpenAI as well as business interests in other industries like hospital administrators, real estate agents, and hotel owners. After getting amended to focus on employment only, Bauer-Kahan chose to hold the bill.

“While we had the votes for passage, getting the policy right is priority one,” she said in a statement last year. “This remains a critical issue and one I refuse to let California get wrong.”