After the new year, when an Amazon warehouse worker showed up to the sprawling facility where he works in Rialto, Calif., he noticed a lot of colleagues seemed to be missing. Stations were empty, he said, and workers were constantly moved around to fill in for those gone. It seemed like everyone was working mandatory overtime.

See our data here.

“Anyone who was there had to do double their work,” said the worker, who asked that we not use his name for fear of retaliation. “I’m pretty sure we were understaffed because a lot of people were calling out sick.”

It turns out hundreds of workers at that Rialto warehouse tested positive for COVID-19 over the past two and a half months, according to worker notifications reviewed by The Markup. Using screenshots of the COVID alerts Amazon sent to one Rialto warehouse worker between Nov. 12, 2021, and Jan. 29, 2022, The Markup tallied 1,038 coronavirus cases in the warehouse. During the same period, the company has rolled back safety and sick leave protocols in its warehouses. Amazon started providing COVID case counts to its California workers in November, the same day the state filed a complaint alleging the company was concealing workforce outbreaks.

At an Amazon warehouse in Rialto, Calif., reports of COVID-19 surged

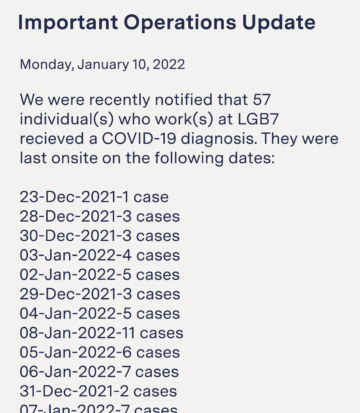

COVID cases included in daily exposure notifications sent to an Amazon worker at warehouse LGB7

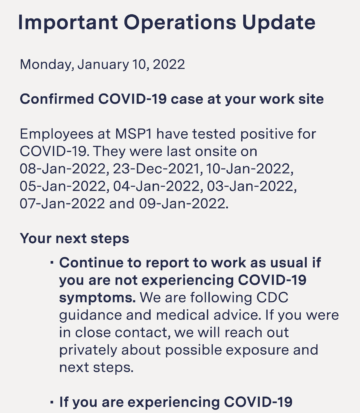

Elsewhere in the country, workers are not necessarily told on a daily basis how many of their coworkers have contracted the virus.

For instance, in California, a notification sent to a Rialto worker on Jan. 10 said that 57 workers had received a positive COVID-19 diagnosis, listing the last date each of those workers had been at the warehouse. Meanwhile, a notification sent on the same day to an Amazon warehouse worker in Minnesota, provided to The Markup, stated that “Employees at MSP1 have tested positive for COVID 19.” There’s no way to tell, from the Minnesota notification, how many employees were sick.

“Amazon has all this information,” said Debbie Berkowitz, former chief of staff and senior policy adviser at the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA.) “They know exactly the risk that workers are facing. They know exactly how many are getting injured and sick. And it’s stunning that they’re deciding to withhold that from their workers.”

COVID case counts inside Amazon’s warehouses have largely been a mystery throughout the pandemic. The last time Amazon publicly published case rates in its warehouses was in October 2020, showing nearly 20,000 of its workers nationwide had tested or were presumed positive for the virus by that point. It didn’t provide data on specific warehouses. Last month, Vice obtained a workforce roster from Amazon’s largest warehouse in New York City that showed roughly 500 workers were out on paid COVID leave. “I had no idea it was this bad,” one worker told Vice.

“This information is so important because workers need to make a calculation about the risk they’re taking when they walk into work every day,” Berkowitz said. “With COVID, it’s the occupational risk that you can bring home to your family and friends.”

Amazon didn’t respond to questions about how many of its workers nationwide have tested positive for COVID or why the company doesn’t provide daily case counts for all its warehouse workers. It did not dispute the daily COVID case notification numbers compiled by The Markup.

In an email, Amazon spokesperson Alisa Carroll wrote that positive cases among warehouse workers “does not mean these individuals contracted COVID at our facility.”

“The country experienced another surge in COVID cases this winter and nearly every company was affected,” Carroll said in a statement. “As we have throughout the pandemic, we work closely with public health authorities and our own medical experts to determine the most effective ways to keep our employees and our communities safe, and we communicate with local health authorities and our employees whenever there’s a new case.”

Working for an Algorithm

Amazon Is Rolling Back COVID Protocols in Its Warehouses. Workers Say It’s Premature

Two Oregon warehouses have been in an active outbreak for nearly 19 months. Elsewhere in the country, warehouse workers report continual cases

Before the Omicron variant hit, Oregon was one of few states that compiled data on COVID cases in Amazon warehouses and made that data public. In the midst of the latest surge, the agency had to reprioritize its outbreak response efforts to focus on “settings with the highest risk for severe disease, death and broad transmission,” according to Erica Heartquist, a public information officer for the Oregon Health Authority. Those settings don’t include warehouses, she said. Before the change in policy, the two longest COVID workplace outbreaks that the state agency had tracked were in Amazon’s PDX7 and PDX9 warehouses—longer even than those in the state’s hospitals and prisons.

The notifications sent to The Markup from California workers provide a rare window into how many people at the company’s warehouses have come down with COVID during the pandemic’s latest surge. In the first full week of December, the Rialto warehouse worker was notified of an average of about four cases each day. By mid-January, it was 45. On one single day, Jan. 17, Amazon sent the Rialto warehouse worker a notification about 61 newly confirmed cases of the virus. According to OSHA, the warehouse has an average annual workforce of roughly 4,400.

The Markup also received and reviewed screenshots of daily exposure notifications sent to a worker at an Amazon warehouse in Stockton, Calif. In that warehouse, which OSHA cites as having an average annual workforce of around 2,700 employees, Amazon alerted the worker to 832 COVID cases among employees over the past couple of months. The alerts peaked on Jan. 20, when Amazon notified the worker of 58 COVID cases.

COVID‑19 cases spiked at an Amazon warehouse in Stockton, Calif.

COVID cases included in daily exposure notifications sent to a worker at Amazon warehouse SMF3

Amazon changed its daily exposure notifications for California workers to include case numbers on Nov. 12, 2021—the same day that state attorney general Rob Bonta filed a complaint against the company alleging it prevented its workers “from fully accessing information regarding COVID-19 cases.” Shortly thereafter the complaint was settled, with Amazon agreeing to pay a $500,000 fine and give its California workers exact case counts.

“We’re glad to have this resolved and to see that the Attorney General found no substantive issues with the safety measures in our building,” Amazon’s Carroll wrote in an email.

That settlement also resolved a lawsuit that California brought against Amazon in December 2020. In the suit, California’s then attorney general Xavier Becerra alleged Amazon withheld information in an investigation into the company’s COVID case rates and safety protocols at its approximately 150 facilities across the state.

“It’s a very serious matter when you have a state attorney general suing a major international corporation for violating a law that is so clearly important and relevant to what is happening to workers on the ground right now,” said Terri Gerstein, fellow at both Harvard Law School’s Labor and Worklife Program and the Economic Policy Institute. “This isn’t a mom-and-pop. This is one of the largest and most powerful companies in the world.”

Going to Work Sick

The Omicron surge in Amazon’s warehouses came after the company spent the past several months easing COVID safety protocols in its warehouses, including halting in-house testing and temperature scans and disassembling some social distancing barriers. And despite Amazon now telling California workers about COVID case counts, several workers have told The Markup that they’re not informed if someone who works near them has been infected, so it’s hard to know when they’ve been exposed.

Amazon’s Carroll wrote in an email that, “To best protect our employees, we immediately kick off contact tracing to determine if anyone was exposed to that individual, and we inform those employees right away and ask them to quarantine with pay.”

The Markup reviewed an in-app message sent to workers on Jan. 7 that said the company was shortening its COVID-19 sick leave policy from two weeks to one week. It said workers would be limited to 40 hours of paid leave if they got the virus. The move followed the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s update of its guidelines in December to say most people infected with the coronavirus could isolate for five days rather than 10.

Shortly after that, the Rialto warehouse worker said, the inevitable happened. Despite being vaccinated, boosted, routinely wearing a mask, and isolating at home with his family when he wasn’t at work, he tested positive for COVID. A couple of days later, his family members got it too.

“I’ve just been going straight to work and back home. I haven’t gone anywhere else,” he said. “Two days before [testing positive], I started getting a sore throat and really didn’t think much of it…. [Then] I woke up with body aches, but thought maybe it was because we stand on our feet so much.”

He went to work but didn’t last the full day. By the afternoon, he was home with a fever and chills, which progressed into severe headaches and a bad cough. And getting approved for sick leave wasn’t easy, he said.

After getting a positive COVID test from a doctor, the Rialto worker said it took more than two hours to reach Amazon’s human resources. The company eventually approved his paid sick leave, although he said he wasn’t paid for those hours of work he missed on the day he left early. According to documentation the worker provided to The Markup, he was given 40 hours of paid sick leave.

Amazon is known for making workers go through an arduous process to get leave, and the company has reportedly terminated workers when attendance software inadvertently marked them as absent, according to a report by The New York Times. According to an NBC News report, one Amazon worker spent up to nine hours on the phone trying to get hold of human resources after falling ill with COVID. Several other workers told NBC News that Amazon incorrectly deducted their accrued vacation time while they were supposed to be on COVID sick leave.

900

Number of comments on Reddit thread detailing troubles Amazon employees had getting sick leave.

In January, a popular Reddit page Amazon warehouse workers use to share stories and get questions answered from other workers about the company’s protocols became so overwhelmed with questions about COVID sick leave that the moderators created a separate “megathread” dedicated to the topic. As of Feb. 9, the megathread had 900 comments from workers detailing scenarios in which they’d spent days trying to secure leave and jumping through hoops to get tests and doctor’s notes to prove they were sick. Several workers said they still went into work sick because they couldn’t figure out how to get approved for leave or extended leave.

Amazon’s Carroll wrote in the email, “To manage the increase in request for leave from our employees, we invested nearly $30 million in improvements, expanded the scope for our call center so they could provide a better customer experience and updated our training and quality programs. These actions have yielded a significant increase in first-contact resolution.” Carroll didn’t provide specifics on the improvements.

“It’s very important for workers to have adequate sick leave because otherwise they’re incentivized to come to work sick,” said Jordan Barab, former deputy assistant secretary for OSHA. And with COVID’s high rate of transmissibility, these types of policies are also important for the entire community, he added, “If you’re infected at work, you can take that home to your family as well.”

The night before the Rialto worker was due back at the warehouse, he said he still felt sick. His fever had subsided, but he was weak and exhausted. So, the worker decided to ask Amazon for an extension to his leave—even though it probably meant no pay for those extra days off since they went beyond the 40 hours of the company’s COVID leave policy.

“I submitted [for the extension] two days ago,” he said. “And I still haven’t heard back.”