Hello, friends,

Who gets tested for the coronavirus? This question is increasingly urgent here in the U.S. as we try to find a path to a post-pandemic economy.

Given the shortage of tests, and the lack of federal coordination, testing in the U.S. varies dramatically by location. Each state’s health department sets its own rules about who is eligible for state testing.

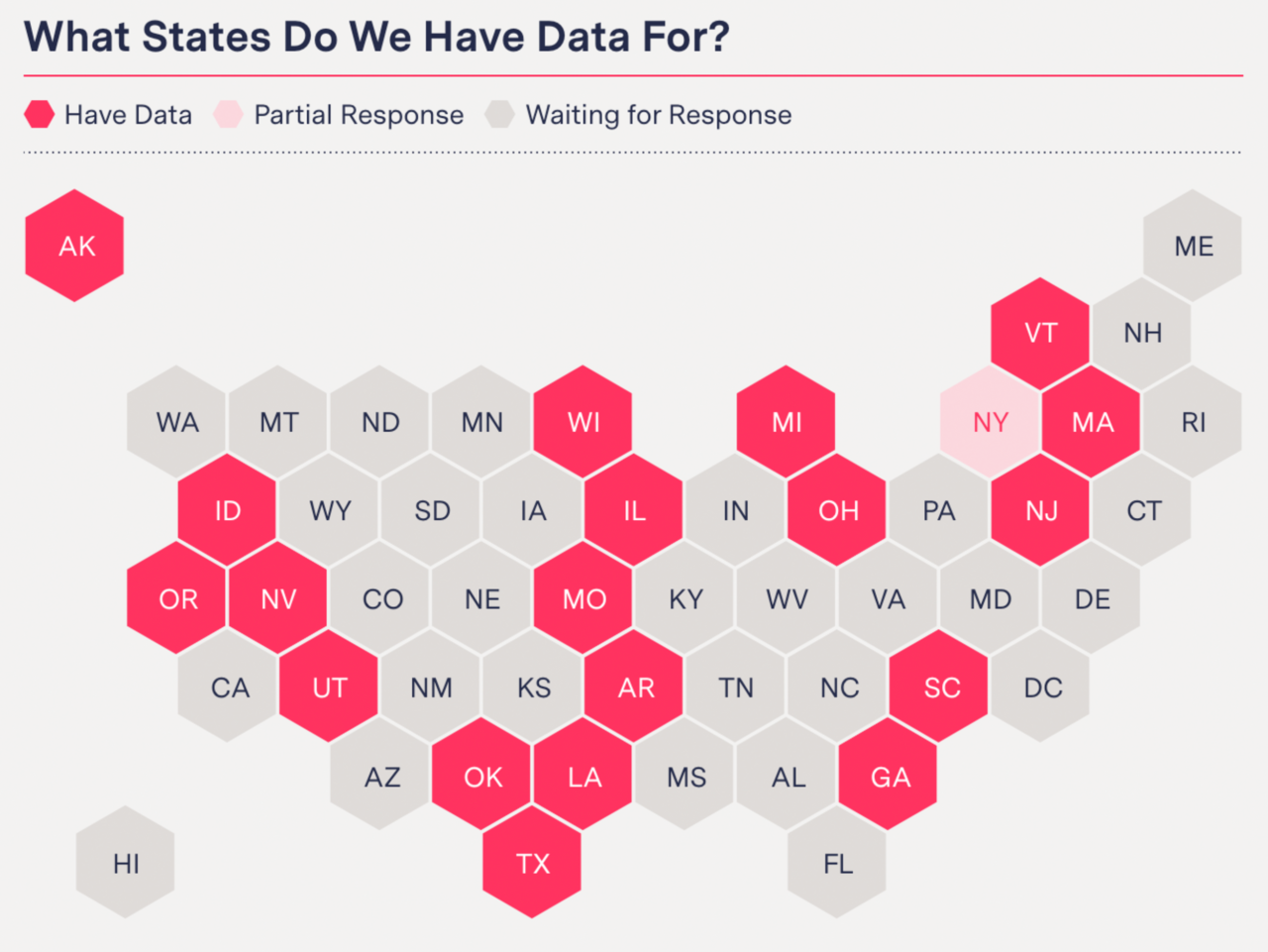

There is nothing more interesting to us here at The Markup than the inner workings of algorithms that have high human stakes. So, one month ago we filed public records requests in 50 states, New York City, and Washington, D.C., seeking their testing algorithms.

So far we’ve obtained records from 21 jurisdictions, and we’ve found stark differences in state testing protocols. A few examples:

- If you’re a senior with a fever, you would qualify for a coronavirus test in Utah but not in Wisconsin.

- If you work with someone who tested positive, you would qualify for a test in Idaho but not Massachusetts.

- If you’re a health care worker in South Carolina, you would qualify for testing if you have symptoms, but in Texas you must have symptoms AND have been in close contact with a confirmed COVID-19 patient.

- Unless you are sick enough to be hospitalized, you don’t qualify for a test in New York City.

For this investigation, reporters Colin Lecher, Maddy Varner and Emmanuel Martinez combed through dozens of documents and categorized them by their testing criteria. We will continue to update that database as we receive new records.

The question remains, though: If you do manage to get tested and the results are positive, how do you alert people whom you have been in contact with recently?

To address this, Apple and Google have proposed technology that would let you notify people who have been near you in recent weeks, even if you don’t know them.

The proposed apps turn your mobile phone into a full-time surveillance device: It would quietly keep track of other phones that have been in Bluetooth range over a rolling two-week period. If you find out you’ve been infected, you can send an alert to all the phones that were recently near you.

Of course, this raises enormous privacy issues. Apple and Google are using some clever cryptography to try to keep the system anonymous. But I was curious about how the system could be exploited—so I canvassed some noted security experts to see what vulnerabilities they had found in the plan.

In my first article for The Markup (woo-hoo!) I describe the pros and cons of the proposal. The pros are that it’s opt-in, it’s mostly anonymous, and no personal information is required for use. Most important: Very little personal data is stored on a central server; most of the information is transmitted directly between cellphones.

However, there are also some major potential problems with the system. Security experts told me that it’s vulnerable to abuse from trolls, spoofing, and advertisers trying to extract data. After all, the ad industry is already using the same types of Bluetooth signals for what they call “proximity marketing.”

“It’s just kind of unfortunate that there’s a whole industry (ad tech) that is already ‘in proximity and watching’ for different reasons,” security expert and creator of the encrypted Signal messaging app Moxie Marlinspike told me.

Any tech-based surveillance system also has a central tension between anonymity and authentication. If the system is truly anonymous, it would be easy for people to sow panic by sending false alerts. “Little Johnny will self-report symptoms to get the whole school sent home,” predicted University of Cambridge security researcher Ross Anderson in his critique of the proposal.

But Apple and Google have said that they would embed their technology in apps built by public health authorities. If those authorities seek to verify users’ identities, their diagnoses, and their movements, then that would likely render many of Apple’s and Google’s carefully constructed privacy protections moot.

Thanks as always for reading! Stay safe and healthy.

Best,

Julia Angwin

Editor-in-Chief

The Markup