Hello, friends,

Two months ago, we started digging into the little-known, roughly $12 billion industry that traffics in data about people’s movements collected from their cellphones. After much sleuthing, investigative data journalist Jon Keegan and reporter Alfred Ng identified 47 companies that harvest, sell, or trade in mobile phone location data.

But they still didn’t have a handle on the most important question: Which apps on people’s phones are selling personal data into this market?

Few people are deliberately, or even knowingly, sharing their location with data brokers. Most often, users give an app permission to track their location for a legitimate reason without realizing that in the fine print of the app’s privacy policy it has disclosed that it may sell that data.

So Jon and Alfred kept digging. Eventually they found several industry insiders who pointed them to one app that they said was a major source of raw location data for the industry: the family safety app Life360.

Life360 markets itself as a way for family members and friends to keep track of each other’s locations and says it is used by 33 million people worldwide. I hadn’t heard of the app before Jon’s and Alfred’s reporting, but when I asked my teenage children about Life360, they were very familiar with it. They said many of their friends used it so that their parents could track their movements.

Of course, Apple and Google phone operating systems also offer ways that users can track each other—with consent—but Life360 promises additional features such as sharing how fast someone is driving and how much battery life someone has left, as well as an SOS button and vehicle crash detection.

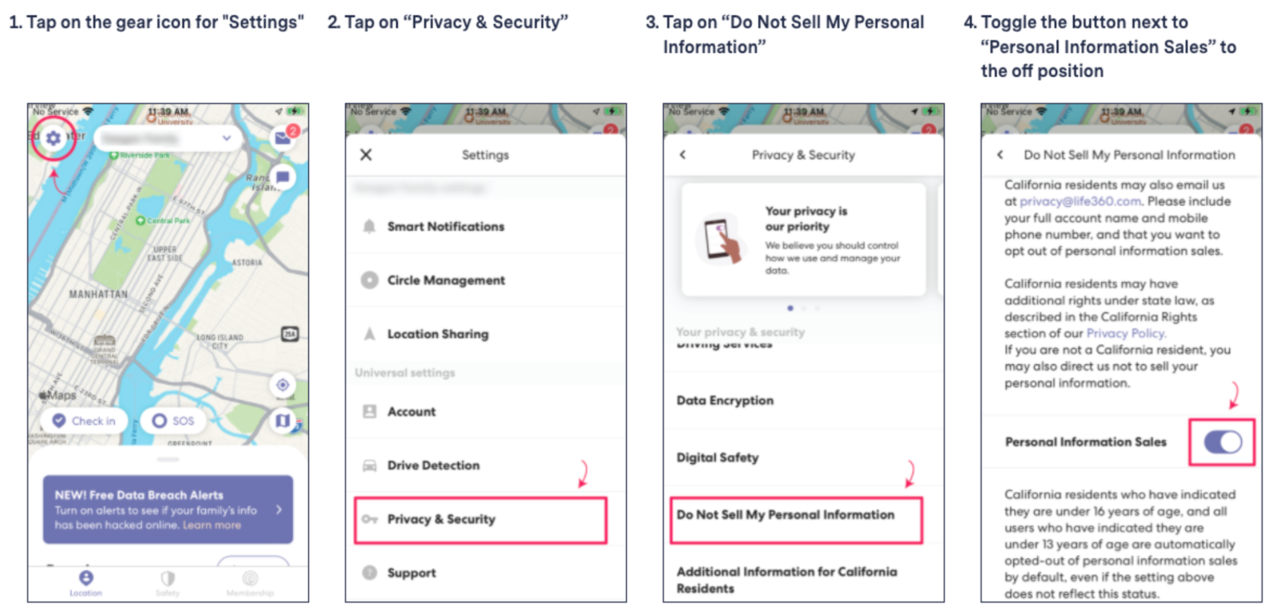

But it turns out that unless Life360 users navigate three menus deep into the app to disable data sales, their location data can be distributed to at least a dozen data brokers, who in turn can sell insights from that data to others.

How to Disable the Sale of Your Location Data in the Life360 App

Life360 founder and CEO Chris Hulls told us that millions of users had opted out of having their data sold.

“We see data as an important part of our business model that allows us to keep the core Life360 services free for the majority of our users, including features that have improved driver safety and saved numerous lives,” he said in a written statement.

According to its public filings with the Australian Securities Exchange, Life360 made $16 million in 2020 from selling location data, plus an additional $6 million from its partnership with Allstate’s Arity, a driving analytics company.

Even so, Life360 is not profitable, reporting a loss of $16.3 million last year. And it has been on an acquisition spree. In 2019, it purchased ZenScreen, a family screen-time monitoring app. In April, it purchased the wearable location device company Jiobit, aimed at tracking younger children, pets, and seniors, for $37 million. And on Nov. 22, Life360 announced plans to buy Tile, a tracking device company that helps find lost items. Hulls said the company doesn’t have plans to sell data from Tile devices, Jiobit devices, or its digital safety services.

But the data that Life360 sells from its family safety app is one of the largest sources of data for the location data industry, according to four former employees of Life360 and its partners. They spoke with The Markup on the condition that we not use their names because they were still employed in the industry. (The Markup has a strict policy of only allowing anonymity for sources who could face retribution for speaking with us.)

They told us that Life360 can share location data within 20 minutes of being collected, and it can be shared “raw” rather than the industry best practice of “hashed” to ensure that it cannot be traced back to an individual user.

“Some of our data partners receive hashed data and some do not based on how the data will be used,” Hulls told The Markup. He confirmed the speed at which data is sometimes shared and said for the most part Life360 relies on contractual obligations that prohibit its customers from re-identifying individual users.

Similarly, Hulls said that Life360 recently instituted a policy prohibiting its customers from selling or marketing Life360’s data to any government agencies to be used for law enforcement purposes but does not have technical measures to prevent the practice.

“From a philosophical standpoint, we do not believe it is appropriate for government agencies to attempt to obtain data in the commercial market as a way to bypass an individual’s right to due process,” Hulls said. However, he acknowledged that it was a challenge to monitor partners’ activities for compliance with the policy.

And that is ultimately the problem with the data location tracking industry. Apps collect extremely sensitive data—researchers have shown that just four unique location data points can identify 95 percent of individuals—and then sell it to data brokers, who can then sell it to whomever they want. There are no laws in the U.S. governing the sale of this sensitive data.

We plan to keep investigating the apps and data brokers that buy and sell your movements. If you have any insights to share about the location data tracking industry, please send them along to Jon Keegan at keegan@themarkup.org.

As always, thanks for reading.

Best,

Julia Angwin

Editor-in-Chief

The Markup