Hello, friends,

Some of the most important problems in our society are not secret. But that does not mean they don’t need investigating.

One of those hidden-in-plain-sight problems is the massive wealth disparity between White and Black families in the U.S. In 2019, White families had an average net worth of $983,400 while the average Black family’s net worth was about a tenth of that, $142,500, according to the Federal Reserve.

One well-documented reason for the gap has been the disparity in homeownership, which has been a key method of building wealth and passing it on to the next generation. The Federal Reserve study found a particularly stark gap in homeownership between young (under 35) White and Black people. In that group, nearly half of the White families owned a home, while just 17 percent of Black families did.

The wealth and homeownership gaps are similar between White and Latino families, according to the Fed.

Some of the homeownership gap is due to disparities in mortgage lending: applications from Blacks and Latinos are denied more often than those from White applicants. And that disparity is powered in part by several algorithms—mainly those created or required by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac—that are a key part of the process of approving and denying loan applications.

The Markup investigative data reporter Emmanuel Martinez has been trying to get to the root of the mortgage lending gap for years. In 2018, he published a landmark investigation at the nonprofit newsroom Reveal showing that redlining in mortgage lending persisted in 61 metro areas even when he controlled for nine different variables including applicants’ income, loan amount, and neighborhood. That investigation landed him and his reporting partner, Aaron Glantz, two of the most coveted prizes in investigative journalism: the Selden Ring and a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize.

The lending industry responded that the gaps between people of color and White applicants could be explained by financial characteristics that were not available in the public data: debt-to-income ratio, combined loan-to-value ratio, and credit score. So, last year, when Emmanuel learned that the first two of those three factors were now part of the public data, he decided to see whether the industry was right. Would these factors erase the gaps?

He spent more than a year analyzing more than 17 million records, running more than 150 statistical regression equations. He found that the industry’s defense didn’t hold water.

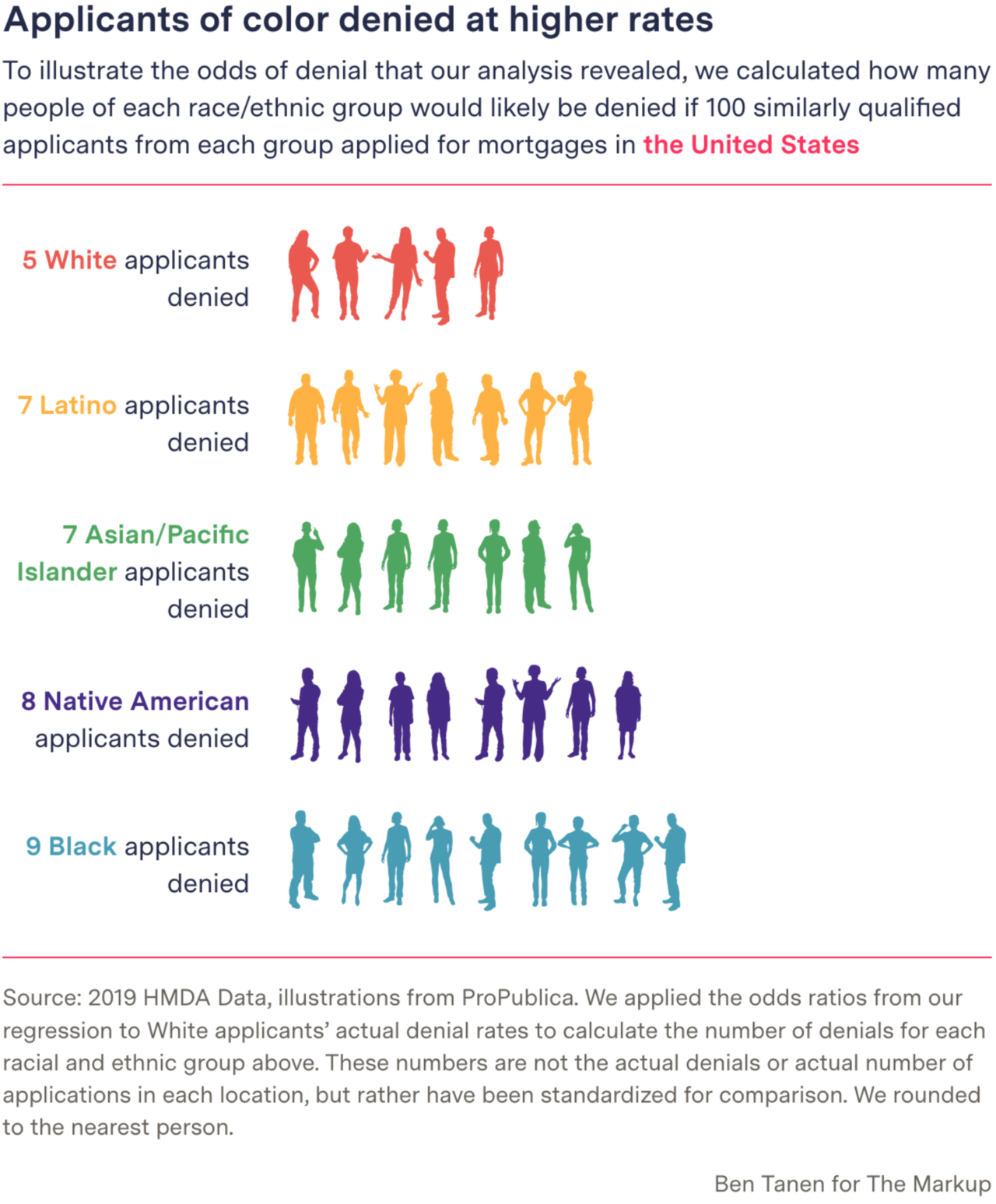

Holding 17 factors steady in a complex statistical analysis of 2019 conventional mortgage applications, Emmanuel found that lenders were 40 to 80 percent more likely to reject an applicant of color than a White applicant.

The resulting investigation by Emmanuel and The Markup investigative reporter Lauren Kirchner, Denied: The Secret Bias Hidden in Mortgage-Approval Algorithms, was published this week. In a first for The Markup, the article was also distributed on the Associated Press newswire and has been published by more than 250 news outlets as of this writing. It was also featured on Marketplace Morning Report with David Brancaccio.

The data revealed significant racial disparities not only at a national level but also in 89 metro areas. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Black prospective homebuyers fared the worst in highly segregated Chicago, where the term “redlining” was born. Lenders were 2.5 times as likely to reject Black Chicago applicants as White ones with similar financial circumstances.

Minneapolis was also unique in being the only metro area where lenders were more likely to turn away applicants of all four racial and ethnic groups included in the data—Black, Latino, Asian/Pacific Islander, and Native American—than their White counterparts.

The lenders with the largest racial disparities included mortgage companies affiliated with the nation’s three largest home builders: DHI Mortgage (affiliated with D.R. Horton), Lennar Mortgage (affiliated with Lennar Corp.), and Pulte Mortgage (affiliated with PulteGroup Inc.). None of the lenders disputed our findings and several expressed commitment to equal opportunity lending. (PulteGroup did not respond to requests seeking comment.)

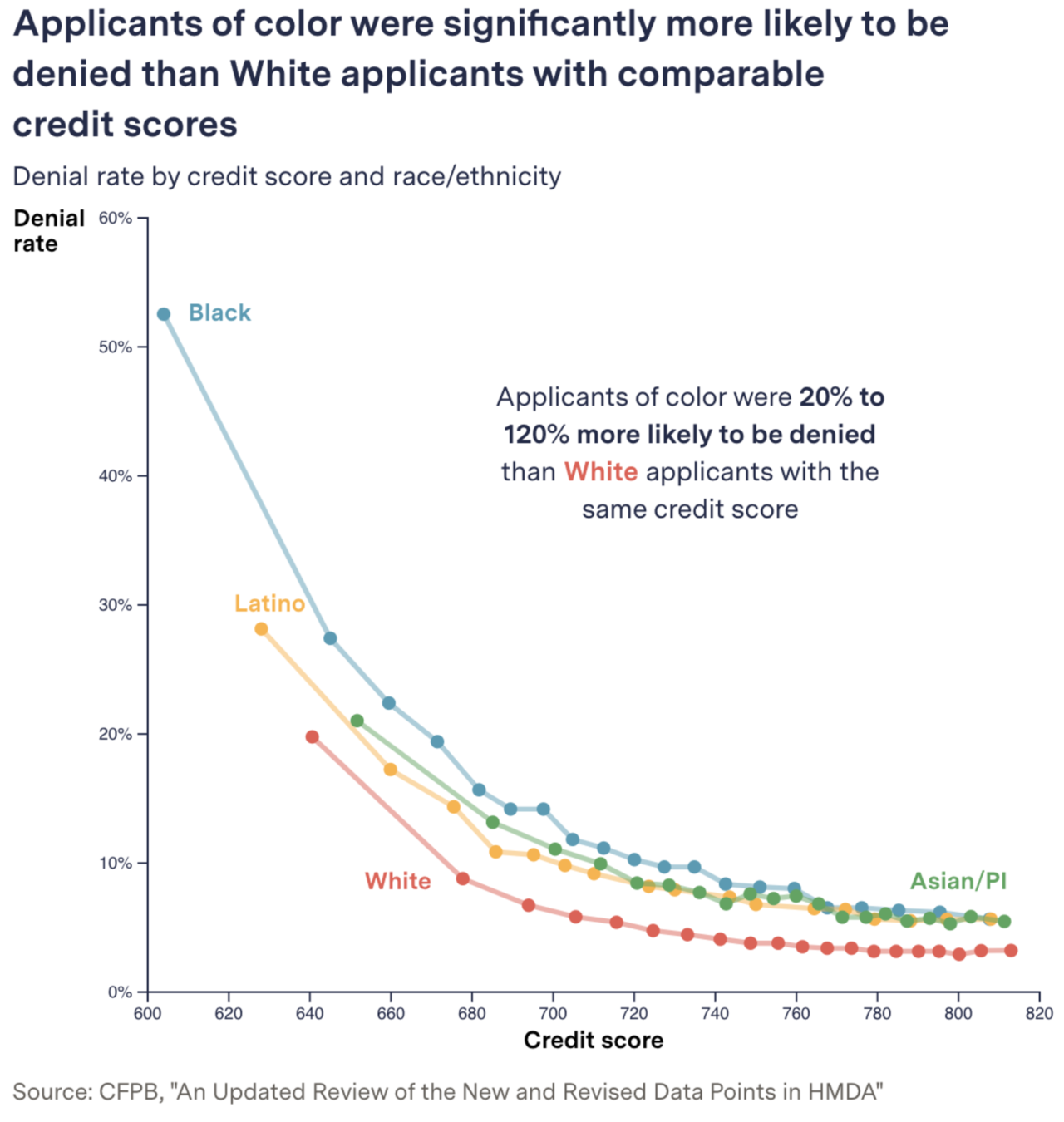

The Mortgage Bankers Association issued a press release this week calling our analysis “flawed” and saying that we had failed to “take into consideration key components that form the backbone of lending decisions, including a borrowers’ credit score and credit history.” (We shared our analysis in advance of publication with the bankers association and other industry groups. None pointed to any flaws in our computations.)

They are correct that the public data does not include credit scores—which lenders report to the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. This field is stripped from the data before it is released because of privacy concerns. However, the bureau’s own analysis shows that people of color are denied loans at a higher rate than White applicants when holding credit scores constant.

Another limitation of our investigation was that we couldn’t see the decisions made by the Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac underwriting algorithms. Our analysis was based on the lending decisions, which occur after the algorithmic decision-making takes place.

To fully answer questions about the racial lending gap we need more transparency. We need to see the credit scores that CFPB currently strips from the data; advocates suggest that the privacy concerns can be addressed by providing buckets or z-scores as the CFPB does with other variables in the data. And we need to see the underwriting decisions made by Fannie’s and Freddie’s algorithms, which CPFB also currently strips from the data.

But even without that additional info, Emmanuel has accumulated a mountain of evidence over the years showing that there are racial disparities embedded in the lending system that powers the American Dream of homeownership.

Our goal is to keep compiling evidence that contributes to the public debate about how to disentangle America’s racial legacy from the algorithms that power its future.

As always, thanks for reading.

Best,

Julia Angwin

Editor-in-Chief

The Markup