Hello, friends,

For my teenage children, YouTube is the Internet. If they want to know about something, they don’t search on Google, they search on YouTube (which is, of course, owned by Google).

And advertisers have noticed. Last year Google made $19.7 billion selling ads on YouTube.

But in our two-part investigation this week, we found that Google has been less than careful about the kinds of YouTube videos it hides from advertisers.

We found that Google has a secret blocklist that prevents results from appearing when advertisers search for YouTube videos related to objectionable keywords such as “heil hitler.”

Investigative data journalist Leon Yin and investigative reporter Aaron Sankin found that this blocklist was full of holes. Many common hate phrases, such as “14 words” and “blood and soil,” were not blocked. And bans were easily evaded—for instance “heilhitler” worked while “heil hitler” was blocked.

And at the same time, Leon and Aaron found that search results for many commercially popular social justice phrases such as “Black Lives Matter” were blocked in Google’s ad buying portal.

When we approached YouTube for comment, the company responded by blocking not only additional hate terms but also dozens of additional social and racial justice terms, including “Black in Tech,” “Black excellence,” and “antiracism.”

In addition, the company also prevented us from investigating further by changing its code so we could no longer identify with certainty which search terms were banned.

To tell the story behind the story, I spoke with The Markup investigative data journalist Leon Yin, a brilliant data scientist who had never worked in a newsroom before coming to The Markup. Leon was previously a research scientist at NYU, a research affiliate at Data & Society, and a software engineer at NASA. At The Markup, Leon builds datasets, designs experiments, and audits algorithms for our investigations.

The interview is below, edited for brevity.

Angwin: Let’s start with this: How did this story come about?

Yin: Aaron and I started looking at one of Google’s ad portals for another story about how Google was suggesting porn keywords to advertisers searching for “Black girls,” “Latina girls,” and other ethnic terms.

So I started entering words into other Google ad portals, including the one that advertisers use to buy ads in YouTube videos. For instance, I knew from previous work that the “White genocide” conspiracy theory was largely circulated on YouTube, and it spread to the point where Tucker Carlson and former president Donald Trump were talking about it.

So I input “White genocide” into the portal, and it returned nothing. Then I noticed that if I removed spaces, it returned something. From there I started looking into the code and found an API where we could type things in programmatically and see what came out.

At first, we couldn’t tell the difference between something that was blocked and something that was obscure and didn’t have any videos associated with it. But we were able to figure out the difference when we looked at the API, because the format of the returned data [for blocked terms] was completely different.

From there we decided to start looking into hate terms. But then I noticed that when I typed “Black Lives Matter” into the portal, it returned nothing. And so from there, we went to several advocacy organizations and asked them for help assembling social justice terms to test—and they gladly gave us keywords to start off with. And that became our second story.

Angwin: Let’s just dive into a little bit more in detail. How did you find the API? And for the non-technical folks, what is an API?

Yin: An API [application programming interface] is a way for different applications to talk to one another. Usually they are external, so, for instance, I can use Twitter’s API to get tweets. But there are a lot of APIs that are internal and are only there to make the site operate, so they’re not documented.

We found the one that powers the specific ad portal that we were looking at by using something called developer tools. This technique, which my colleague Surya Mattu taught me, allowed us to listen for what are called network requests while we were typing words into the portal. We could then isolate an API call being made, which allowed us to pick it apart and figure out how to reuse it.

Being able to reverse-engineer the API allowed us to test lots of terms at once.

Angwin: After you went to Google for comment, they turned off your ability to test for blocked terms. What exactly did they do?

Yin: When we reached out to Google, they told us they had made a mistake and they would block the bad terms.

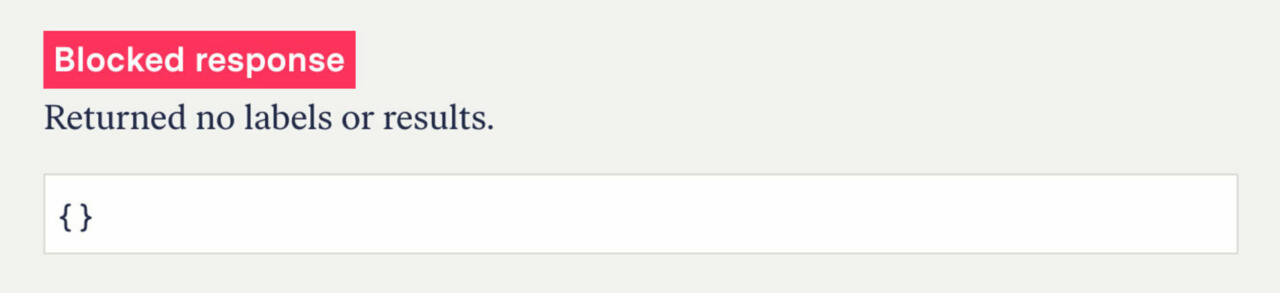

When we checked, we saw that they had blocked the additional terms, but in a completely new way. Before we found that for blocked terms, the portal returned just two curly JSON brackets and that’s it.

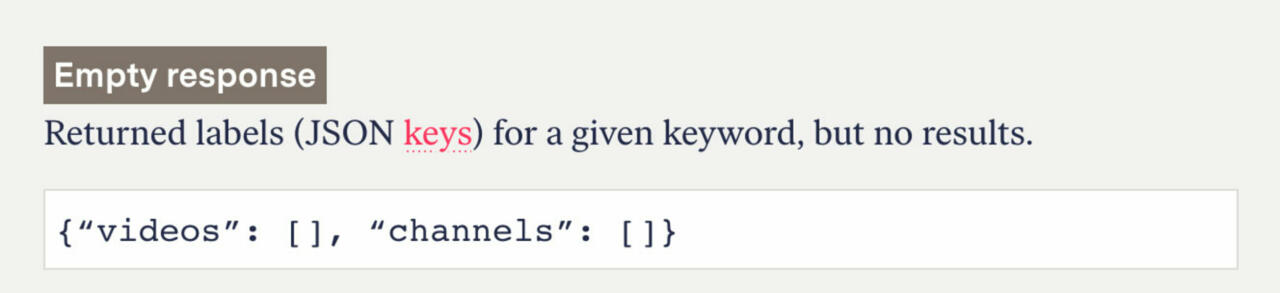

However, the new block returned the same result that we saw for obscure search terms where no videos were available for advertisers—the results were two empty fields within the JSON brackets.

This was completely different from what we had seen previously. And it makes future work difficult because it’s hard to disentangle what is blocked and what is obscure.

Angwin: What did you learn about the nature of the blocklist while researching it?

Yin: We noticed that there’s a hierarchy, where certain terms get blocked but a slight variant won’t be blocked. One of the examples that we cite is “White nationalist” still is blocked, but not “White nationalists” or “White nationalism.”

We also noticed that certain terms are blocked by association. So any phrase mentioning “Muslim” is blocked. So innocuous things like “Muslim fashion” or “Muslim parenting” are blocked, even though they’re commercially viable. The same was not true for other religion pairs like “Christian fashion” or “Jewish fashion.”

We also noticed the strictest kind of block was a substring block. For example, “sex” will be blocked automatically, even if it’s part of a longer word. For instance, both “sex work” and “sexwork” were blocked.

This makes us think that Google is probably using regex, or regular expressions, which are used for text matching. But it’s a very poor way to do matching because you have to think of the expressions in advance. So what we found is that they have a very primitive technology that’s very manually updated, and there’s probably a more sophisticated way of doing it.

And then there’s another question of, well, why do it at all? This is the most downstream form of content moderation, in my opinion, because it’s assuming that the content already exists, and it’s just adding a blindfold for advertisers.

It’s like instead of cleaning your yard, you’re just telling your guests to walk through the back entrance. It’s not like you’re actually cleaning your yard. It’s still dirty and hazardous, but your guests are now going through the back.

Angwin: You’ve studied YouTube and hate on platforms for a long time. What was most surprising to you?

Yin: There were two things that were surprising. The first was that there are a ton of re-uploaded deleted videos on YouTube. A lot of personalities that are de-platformed for hate speech pop up again when fans upload their videos.

It’s interesting because I know for a fact that YouTube uses fingerprinting technology for copyright violations, so they can automatically take down content for copyright owners, but they don’t apply the same technology to hate-based content.

The second surprising thing was their reaction to the social justice keywords that we found they were blocking, such as Black Lives Matter. Instead of removing words from their blocklist, they instead doubled down and blocked even more terms, like “Black excellence,” and continued to block anything paired with “Muslim.”

Last year, YouTube CEO Susan Wojicki said, “We believe Black lives matter and we all need to do more to dismantle systemic racism.” But it seems they are not really dismantling anything.

As always, thanks for reading.

Best,

Julia Angwin

Editor-in-Chief

The Markup