Hello, friends,

When was the last time someone snail-mailed you the password you needed to access a website or called you on the phone to verify information you entered online? For many people the answer is probably at least two decades ago. But for the more than 30 million Americans who have applied for unemployment benefits recently, it’s far more likely to have occurred in the last few weeks.

As The Markup reporter Colin Lecher and audience engagement editor Mia Sato report this week, the online unemployment systems are antiquated, arcane, and buckling under the strain of an unprecedented deluge of applications.

In an apparent effort to combat fraud, Colin and Mia found that many states are using verification protocols, such as phone calls and passwords by mail, that are thwarting applicants’ ability to quickly get needed benefits.

George Wentworth, senior counsel at the National Employment Law Project, who has studied unemployment systems, said states are taking steps “in the name of fraud, waste, and abuse” but that he would hope that given the scale of the crisis, “responsible administrators would be dialing back.”

Consider Pennsylvania, where applicants were supposed to sign up online and then receive a PIN number through the mail. Some workers waited more than a month for the PIN to arrive.

The state’s labor department recently recommended that applicants allow at least three weeks for a PIN to arrive before presuming it’s lost and requesting a second one. The officials have since said they’ve caught up with the swell of applicants.

Or consider New York, where many applicants were required to call the unemployment office to verify details of their application after filling out the online form.

Ciara Wardlow, 22, who lost work as a video editor, said she got an automated call, days after filling out an online application for unemployment, telling her to wait for a member of the staff to reach her. Weeks later, she’s still waiting. “It’s just very, very frustrating,” she said.

In response to The Markup’s request for comment, the New York Department of Labor provided a public statement that said there have been “a large number” of claims that are incomplete and need to be processed over the phone. The state said it is taking “a major call-back initiative to proactively call New Yorkers” who have not finished their claims.

Other states are trying to slow the tide of applications by shutting down for hours at a time to process payments or by designing complicated systems to limit the number of people who can apply simultaneously.

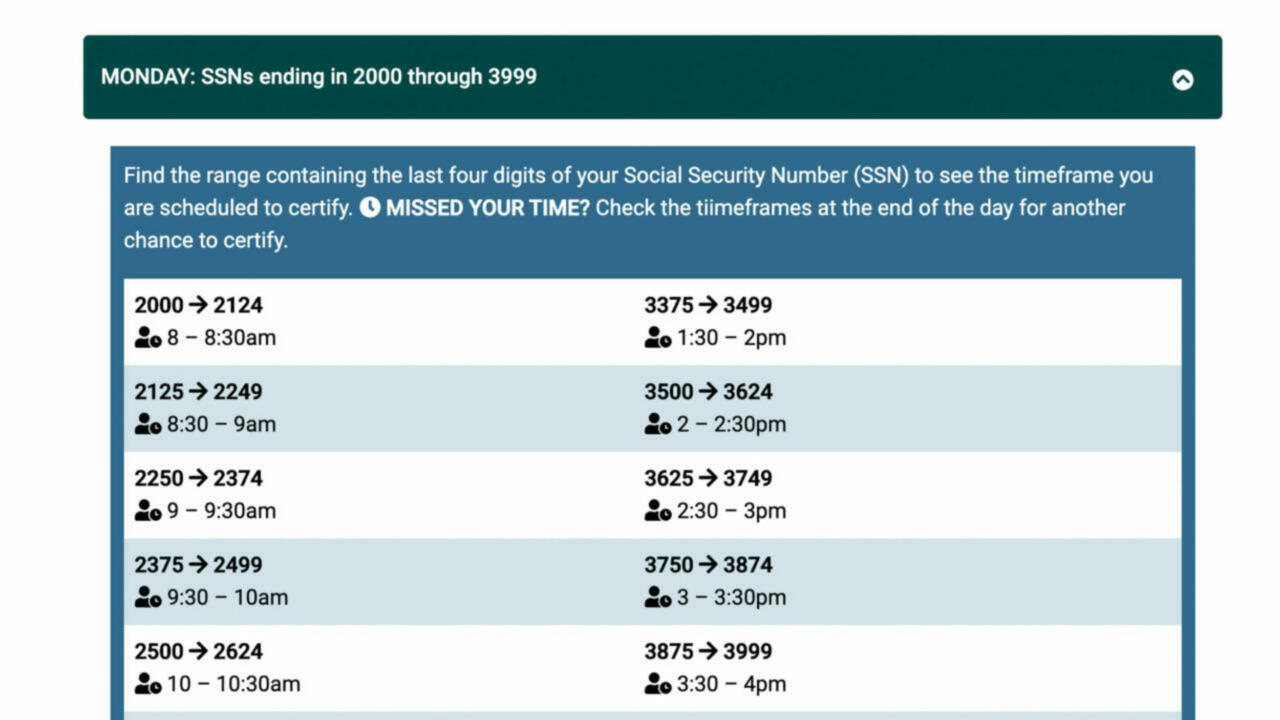

Some states are assigning people to application windows on different days based on the first letter of their last name, while New Jersey assigns applicants a half-hour window in which to certify or claim benefits based on the last four digits of their Social Security number.

In a world where people are used to the idea that most transactions—whether it is ordering lunch or asking for a date—can take place with a tap of their phone, state unemployment systems feel like a throwback to the ’90s.

Updating custom computer systems isn’t cheap. And certainly, state governments, many of which are struggling to pay their debts and obligations, can legitimately argue that their funding is inadequate. Consider Nevada, where the budget for the unemployment insurance administration program has been repeatedly slashed largely because of decreased federal funding.

But in one of the richest nations on earth, there is also more to the story than funding. According to a 2017 report from the National Unemployment Law Project, many states have been purposely restricting eligibility for years, making it harder to get approved or to appeal and cutting the length of time people could receive benefits. The move to online claim filing exacerbated the problem, the study found, with difficult-to-complete application systems responsible in large part for the decline in many states.

The technical and legal barriers may have denied benefits to millions of people, according to a report from the Economic Policy Institute published last month. The study found that for every 10 people trying to apply for unemployment, three to four couldn’t get through the system to make a claim, and another two out of 10 said the process was too complicated to try.

That’s a failure rate of more than 50 percent. And that’s why we at The Markup are committed to monitoring these automated systems on behalf of the public—the stakes are too great to ignore.

As always, thanks for reading.

Best,

Julia Angwin

Editor-in-Chief

The Markup