Hello, friends,

This week we published our first collaboration with The New York Times—an investigation into the algorithmic software that assesses people applying for housing.

When we first heard that landlords were buying reports from companies that use software to assign a “risk score” to prospective tenants, we immediately wanted to find out if those reports were accurate and unbiased. The Markup investigative reporter Lauren Kirchner and I had previously investigated risk scores assigned by algorithms in the criminal justice setting—and found they were often inaccurate and were biased against black defendants. Was something similar happening to tenants?

We began our investigation by looking for data we could analyze. Lauren sent public records requests to 88 public housing authorities, seeking their contracts with tenant screening companies and information about whom they had accepted and rejected, and why.

But privacy laws protecting people who receive public benefits prevented us from accessing the kind of data we had been able to obtain for criminal risk scores. So we had to find another way to examine the industry.

Luckily, this is one of the few areas of the big data economy where a federal law is at work. The Fair Credit Reporting Act—signed into law by Richard Nixon—gives people the right to see their credit reports and challenge any information in it that they believe is inaccurate.

Regulators have said the law also applies to tenant screening companies, which must “follow reasonable procedures to assure maximum possible accuracy.” And that’s where we found our dataset: all the people who had filed lawsuits against tenant screening companies for inaccurate reports.

Lauren pored over hundreds of lawsuits in which applicants had sued some of the more prevalent tenant screening companies under the Fair Credit Reporting Act. In typical Markup fashion, we ended up building a tool to help automate a cumbersome process: Investigative data journalist Surya Mattu wrote a program that downloaded each case’s docket and court complaint, converted the complaint PDF into searchable text, and highlighted those that contained search terms relevant to our investigation.

We ultimately refined our dataset to about 150 cases that were on point. (Also in Markup fashion: All of them are available on Github and DocumentCloud.) And while that is not a huge sample for a $1 billion industry, it did provide a window into how these screening reports often fail.

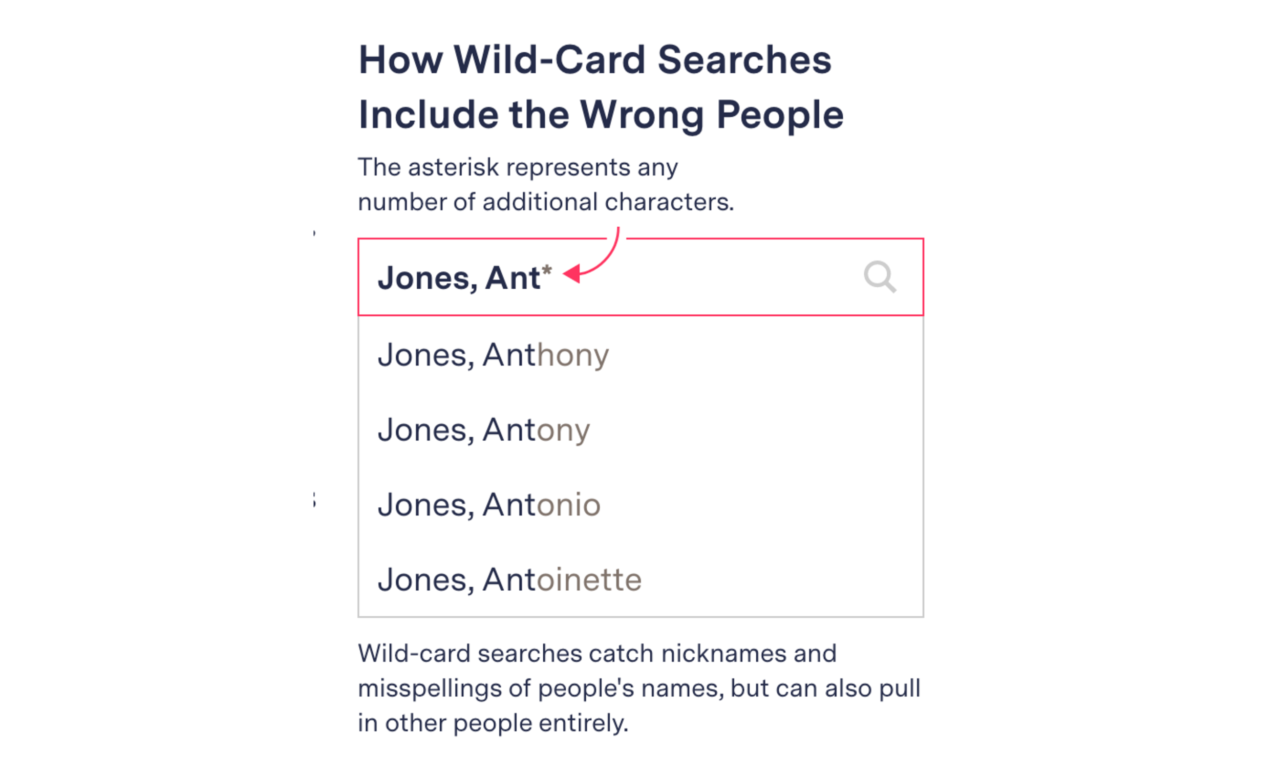

We then teamed up with New York Times reporter Matthew Goldstein, and together he and Lauren found patterns of sloppiness, with the records of people with different names, different dates of birth, and living in different states being assigned to prospective tenants. Some companies used “wild-card” searches, which gather all names that start with the same few letters. For instance, one screening company conducted a search for records about Terrence Enright by searching for Enright, Ter* and Terrence, Enr*—which resulted in an incorrect match with a Teri Enwright, who had an eviction record in another state.

The mistakes can be particularly acute for members of minority groups, which tend to have fewer unique last names. For example, more than 12 million Latinos nationwide share just 26 surnames, according to the census.

Consider Marco Fernandez, who is suing tenant screening company RentGrow for including information in his report from a Mario Fernandez Santana. Marco lives in Maryland, works for the military and has a top-secret security clearance, while Mario is on a federal watch list for suspected terrorists or drug traffickers, lives in Mexico, and has a different date of birth, according to the lawsuit.

“These matching algorithms treat Hispanic names just like a mix-and-match,” said Fernandez’s attorney, E. Michelle Drake.

Many of these mistakes could be avoided if tenant screening companies were forced to adhere to the same standards as credit reporting agencies. After a settlement with 31 state attorneys general, the big three credit bureaus agreed in 2017 to match records using name, address, and Social Security number or date of birth.

The tenant screening industry has not developed its own uniform screening accuracy standards, leaving applicants scrambling to try to correct the errors after the fact. With an estimated 2,000 background screening companies in the market, it is not possible for applicants to obtain and correct all of their reports in advance. Instead, they learn about errors only after a rejection.

Federal law requires landlords to tell tenants the name of the company that produced a negative report about them, but not to provide the report. So the rejected applicant must then go to that company to obtain the report and get it corrected. The screening company has 30 days to respond, and by then, a landlord may have given the apartment away.

“It’s just crazy that you can’t get immediate results,” Andrew Guzzo, a consumer lawyer who has filed numerous federal lawsuits against background screeners and other consumer reporting agencies, told us in an interview.

The trade group for the industry, the Consumer Data Industry Association, told us that the errors we found weren’t evidence of any systemic problems—a claim we couldn’t verify because the screening companies don’t provide their error rates. When they get sued for mistakes like these, we found, they almost always settle, and lawyers for the plaintiffs told us that the companies typically require the plaintiffs to sign a nondisclosure agreement.

There is no denying, though, that people are being harmed by sloppy data practices in the tenant screening industry. Our investigation examines the human toll with the best available data we could collect—and until there is more transparency in this industry, that is the best visibility we can provide to the public.

As always, thanks for reading!

Best,

Julia Angwin

Editor-in-Chief

The Markup