When Benjamin Sowers lost his job in the service industry last year due to the pandemic, he and his fiancée, Keely Reed, brainstormed a new career: starting a food truck serving charcuterie and sandwiches, to be stationed outside Reed’s family’s vineyard in Hood River, Ore. As the opening date in April sped ever closer, the truck, called Wheels, needed a bank account. To open one, the couple needed an employer ID number. To get it, Reed did what just about anybody would do.

She googled it.

“The first thing that popped up said something .gov, -gov,” she told The Markup by phone. “I thought, ‘Great, this is it.’ “

She clicked it and filled out her information and paid the $250 fee the site requested. She had fallen into a trap, one set by the owner of ein-gov.tax-filing-forms.com, which paid Google to show its ad in the results for her search for “online employer identification number”—and place it above the website of the IRS, the agency that distributes EINs online for free.

Reed had inadvertently stumbled into a cottage industry of sites that charge high premiums for what are otherwise free or inexpensive government services. It’s an industry that continues to use Google’s ad section, despite blatantly violating Google’s stated policies, and in some cases, the law.

Google’s ad policy states, “Promotions for assistance with applying or paying for official services that are directly available via a government or government delegated provider” aren’t allowed. Yet The Markup found a swath of examples of ads that appear to do just that.

Google has “removed all of these ads for violating our policies,” Google spokesperson Christa Muldoon said, after The Markup provided the company with the ads. “We prohibit ads that mislead users by implying an affiliation with a government agency.”

Muldoon didn’t respond to a question about why the ads were able to violate Google’s policy.

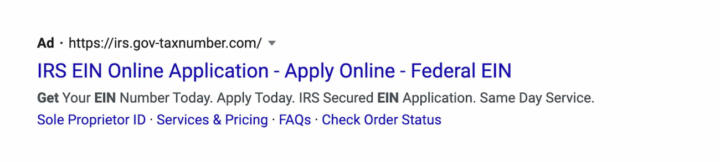

Along with the site that fooled Reed, Tax Filing Forms also operates irs.gov-taxnumber.com—a URL that contains “irs.gov” but isn’t affiliated with the IRS. The Markup found ads for that site on Google in search results for “how to get ein.” Tax Filing Forms’ websites share the subdued design of government websites—enough that Reed didn’t pick up on what happened until her banker raised a red flag over a multiday wait time. (The IRS provides EINs right away.)

Reed complained to the company by email and says she was promised a refund, minus a $75 “processing fee,” but says it hasn’t arrived.

Tax Filing Forms didn’t respond to multiple requests for comment.

A similar ad ensnared Mason Bain, who was moving to Georgia in March. When he went to change his address, he googled “USPS change address” and clicked on one of the first links he saw. It was an ad for a site that charged him $59.03—well above the $1.05 the U.S. Postal Service charges. Bain, who doesn’t remember the exact name of the site he clicked, kept his receipt, but it doesn’t contain the name of the company or site.

Numerous Google ads for searches like “change my address USPS” return third-party sites whose fine-print indicates they charge a high fee.

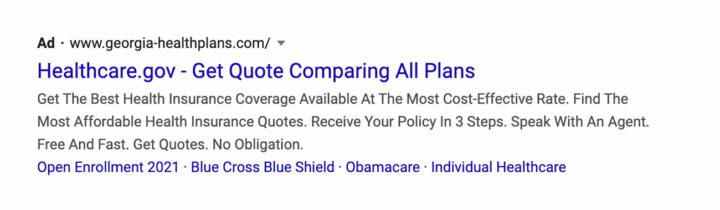

The Markup also found misleading ads for health insurance, purporting to sell “COBRA”—a type of insurance laid-off workers can buy only through their former employer, not from an online vendor. Other Google ads featured the address of the official government health insurance exchange “Healthcare.gov” prominently in big blue type but were actually third-party sites.

“Unfortunately in the age of COVID-19 we have seen what appears to be a rise in fraudsters and scammers trying to market bogus healthcare policies and programs. It is sad when these criminals seek to prey on vulnerable persons who are simply trying to make sure they and their loved ones are protected from the high cost of health care services,” Matthew Smith, the executive director of the Coalition Against Insurance Fraud, told The Markup.

If a reasonable consumer is likely to be deceived about the official status of something, that can be against the law.

Rebecca Tushnet, Harvard University

The federal agency that administers rules about COBRA told the Markup that it “is concerned about reports like these on the misleading sale of ‘COBRA insurance,’ ” said Grant Vaught, a spokesperson for the Employee Benefits Security Administration. He advises consumers to contact their state’s insurance regulators “if they believe they are being targeted by fraudsters looking to sell them bogus insurance.”

A person who picked up the phone at Health Plan Options Today, the company behind the “We provide COBRA Insurance” ad, who said his name was Damian, acknowledged that the company doesn’t sell COBRA insurance but said he wasn’t familiar with the company’s Google ads. He said callers were never confused thinking that the company provides COBRA insurance. The company didn’t respond to an emailed request for comment.

Rebecca Tushnet, a law professor at Harvard who studies advertising, reviewed the ads in this story at The Markup’s request. “They definitely have the potential to be deceptive,” she said. “If a reasonable consumer is likely to be deceived about the official status of something, that can be against the law.

“There are specific laws against impersonating federal officials, but general advertising law also bars false, material representations—so any time a false implication of official status would be received by a substantial number of reasonable consumers and material to them, that would violate the law,” Tushnet said.

Microsoft, which sells search ads for its own Bing search engine as well as for privacy-focused search engine DuckDuckGo (Disclosure: DuckDuckGo is a contributor to The Markup), also showed ads for getting an EIN with “irs” or “gov” in the website addresses and ads offering to sell COBRA health insurance.

“We take fraudulent ads very seriously. Microsoft bans such content, including what can be reasonably perceived as being deceptive, fraudulent or harmful to site visitors,” John Cosley, a senior director in Microsoft’s advertising division, said in an email, citing Microsoft’s policies against misleading ads, which it updated last year to ban third-party ads for government services. “We are investigating these results,” he said.

Like Google’s, Microsoft’s policies explicitly ban ads for private change-of-address sites. However, unlike Google, Microsoft appears to abide by that policy; The Markup wasn’t able to find any ads for private change-of-address sites sold by Microsoft.

DuckDuckGo spokesperson Kamyl Bazbaz said, “Our ads are serviced by Microsoft advertising,” which sets the ad policies and enforces them.

Ads Impersonating the Government Could Be Illegal

By and large, it’s legal to offer help using services also provided by the government. That’s what many of these sites say they are doing in the small-print disclaimers that generally appear on their sites. Dené Joubert, an investigator with the Better Business Bureau, Great West and Pacific, rattled off a list of six additional topic areas, like boat registration, where companies heavily advertise similar services, “doing the work the consumer could do themselves,” Joubert said. But, she said, “most follow through” and actually perform the service.

That wasn’t either Reed’s or Bain’s experience. Reed got the EIN for her fiancé’s food truck directly from the IRS. Bain said his mail only began to be forwarded after he changed his address through the official USPS website.

The disclaimers on sites like these often note that they’re not a government agency. But that’s not always enough to make them legally kosher, experts say. “The doctrine is that the disclaimer has to work. If a substantial number of consumers are still being deceived, your disclaimer didn’t succeed; it didn’t become a part of the overall message,” Tushnet told The Markup.

There are examples of the government taking action on such scams.

Last year, the Federal Trade Commission sued On Point Global, a company that allegedly advertised websites via Google search where you could renew your driver’s license, buy a fishing license, or determine if you were eligible for public benefits like Section 8 housing. But in fact, when people signed up for any of those services, usually for more than $20 each, On Point would send them a PDF “guide” containing publicly available information on how to complete the task through the standard government site.

This was lucrative. Selling PDF guides earned the company $63.2 million in less than two years, according to court documents. Other services, like providing “assistance” in filing change of address forms, earned $17.1 million.

It’s not clear how much On Point Global spent on Google ads.

The case is still pending in U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Florida; in court filings, On Point Global denied that its websites were misleading or illegal, saying they disclosed that they weren’t affiliated with the government and never promised to provide services. (On Point’s former CEO, Burton Katz, didn’t respond to a request for comment sent to his lawyers. Melanie E. Damian, the lawyer appointed by the court to run On Point until the case is resolved, also didn’t respond to a request for comment.)

In the past few years, investigators have found networks of abusive, misleading Google ads for crisis pregnancy centers impersonating abortion clinics, high-priced lead generators masquerading as local locksmiths, and shady placement services that directed patients to secretly affiliated rehab centers.

And fraudulent health care ads have long plagued Google search results.

A 2019 Philadelphia Inquirer investigation highlighted a woman who clicked a private “Healthcare.gov” ad, thinking she was dealing with government-approved plans, and ended up with a plan that didn’t cover her preexisting conditions. One congressional investigator, acting as a secret shopper, told a broker he had diabetes but was sold a plan that didn’t cover it.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, which runs Healthcare.gov, also “has coordinated with Google to remove ads unaffiliated with the agency that use the address healthcare.gov,” agency spokesperson Enrico Dinges told The Markup.

Google told U.S. senator Bob Casey in November 2019 that it would take the step of banning “false ads suggesting they were healthcare.gov, but led consumers to another website,” Casey’s spokesperson Aisha Johnson told The Markup.

Nevertheless, this March and April, The Markup found three ads with wording like “Healthcare.gov—Get Quote Comparing All Plans” and “Healthcare.gov 2021 Enrollment—Compare Affordable Plans Now,” which led to private sites.

Those ads already violate Google’s existing policies, but company spokesperson Muldoon said that Google recently announced a new healthcare-specific policy that would require anyone advertising healthcare plans to be licensed to sell insurance.

Government Agencies Have to Work Around the Ads, and Sometimes Pay to Compete

State insurance regulators, plus several federal agencies, are beginning to pay attention to misleading insurance marketing, including to Google ads in particular, Peg Jasa, a spokesperson for the Nebraska Department of Insurance told The Markup.

The IRS’s own website warns, “Beware of websites on the Internet that charge for this free service,” evidently seeking to prevent the situation Reed found herself in. The IRS did not reply to several requests for comment.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, which also runs the federal health insurance exchange, has taken a different tack: It pays Google to ensure that the real Healthcare.gov appears on the first screen of results, with its own ads. The agency wouldn’t say how much of its advertising budget went to these defensive ads.

The U.S. Postal Service “occasionally receives customer complaints regarding the cost the customer paid to the website agents,” James Wilson, the U.S. Postal Service’s director of addressing and geospatial technology, told The Markup in a statement. But, he said, there’s little that the agency can do beyond taking “appropriate steps” to counteract those who “misuse USPS trademarks or make false claims of affiliation with USPS in their efforts to draw in consumers.”

MyMove, the company that runs the Postal Service’s online change of address portal, pays Google to appear above the private ads too. (USPS spokesperson Sara Martin said the amount was “proprietary.”)

Bain blames himself in part for not using the real change-of-address site. “Honestly, the whole situation could’ve been avoided if I were just a little more careful. I’m pretty conscious about what I do online, so like I said, I’m really kicking myself over this one.”

But, he adds, “I’d say Google allowing these types of ads to run so [high up] on their website is pretty scummy, especially for such a large company.”