On her first day as Instacart’s new CEO in early August, Fidji Simo, a former Facebook executive, acknowledged the tumultuous relationship the grocery delivery company has at times experienced with its workers. Publishing an open letter, she offered change to delivery workers, whom the company treats as independent contractors, not employees.

“I want to be a thoughtful and open partner,” she wrote. She added that workers could email her suggestions on improving working conditions, saying, “My team and I will read every note, and I’ll respond to as many as I can.”

But members of Gig Workers Collective, a group of more than 13,000 gig workers that formed to advocate on behalf of app-based food and grocery delivery workers for companies like Uber Eats, DoorDash, and Shipt, say little has changed at Instacart.

“We were optimistic that there was positive change on the horizon,” said Willy Solis, an Instacart worker and lead organizer with Gig Workers Collective. “But our initial optimism was dashed.”

Instacart, founded in 2012, has amassed $2.7 billion in venture capital funding. During the coronavirus pandemic, the company said business boomed, with the number of orders going up by as much as 500 percent, prompting it to hire more than 500,000 new delivery workers. While it’s unclear how profitable Instacart is, and grocery delivery businesses overall have begun to slump, the company has indicated it plans to go public before the end of the year.

Yet, advocates say, Instacart workers are not seeing their pay improve—the fundamental issue at play in a new #DeleteInstacart campaign launched by Gig Workers Collective. The group is asking customers to support delivery workers by boycotting the company until it “rectifies the genuinely inequitable manner in which it treats its shoppers.” (“Shopper” is Instacart’s term for delivery worker). The collective is also planning a walk-off on Oct. 16, asking workers to avoid delivering for the company.

“We take shopper feedback very seriously and remain dedicated to listening and learning from our community to improve the Instacart shopper experience,” said Natalia Montalvo, Instacart’s director of shopper engagement and communications. “While historically the actions by this group have not resulted in any disruption or impact to our service, our relationship with all shoppers is incredibly important and we’re deeply committed to doing right by them.”

Rebecca Givan, an associate professor at Rutgers University School of Management and Labor Relations, said the labor clash is not unique to Instacart workers—she’s seen an overall uptick in gig-worker-led boycotts, strikes, and walk-offs.

As the workers are squeezed more, they start to learn successful organizing strategies

Rebecca Givan

“As the workers are squeezed more, they start to learn successful organizing strategies,” Givan said. “The workers are explicitly asking for customers to use another option. This is something that is a little bit different when we’re talking about gig workers, because it’s frictionless for both the workers and the customers to switch to another app.”

Instacart workers have taken various forms of collective action against the company in the past. In the beginning of the pandemic, workers demanded hazard pay and access to paid sick leave; and before that, they protested over low pay and how the company allocates workers’ tips.

In this latest round of unrest, Gig Workers Collective has five specific demands, which focus on working conditions and Instacart’s pay structure. The group published this list in an open letter to Simo in mid-August.

Simo has been “consistently reading and responding to emails” and has conducted “a number of one-on-one conversations” with workers, Instacart’s Montalvo said. But Solis, from Gig Workers Collective, said individual workers he’s spoken to have gotten “canned responses” from the CEO, and the collective has yet to hear back.

“At the end of the day, it was nothing more than lip service,” Solis said. “We need more than placating banter.”

How Much Are Instacart Workers Paid?

Workers say that as pay has declined over time, their earnings have become harder to predict and understand.

When Kelly Harris started working for Instacart in Columbus, Ohio, in 2017, her pay would fluctuate based on what Instacart said was customer demand. She said that back then it was easier to predict what her pay would be: $0.40 per item in each order, plus a set price per order. That price would go up or down depending on what Instacart deemed busy times.

In 2018, Instacart changed its pay structure by getting rid of “busy”-time pricing and the $0.40 per item payments. The company started relying more heavily on its algorithm to calculate pay. Workers would get at least $10 per order, and the price could go up from there, but workers say how much and when seemed to be arbitrary. Harris said she began earning less.

Then, in 2019, Instacart changed again—lowering the minimum pay from $10 to $7 per order and bundling up to three orders together for that $7 baseline (or whatever price the algorithm had set).

“The kind of money that I was making in 20 to 30 hours then, I would probably need to work 100 hours now,” said Harris, who’s relocated to Steubenville, Ohio. “I’ve seen a 70 percent pay cut over the years. It’s really not worth it; it’s not reliable anymore.”

I’ve seen a 70 percent pay cut over the years. It’s really not worth it

Kelly Harris

Montalvo didn’t respond to questions about how the company’s algorithm calculates worker earnings but said, “There are many considerations for every order that needs to be taken into account when determining batch pay—including the volume of customer demand, geographic profiles, retailer mix, items, weight, and projected delivery times.”

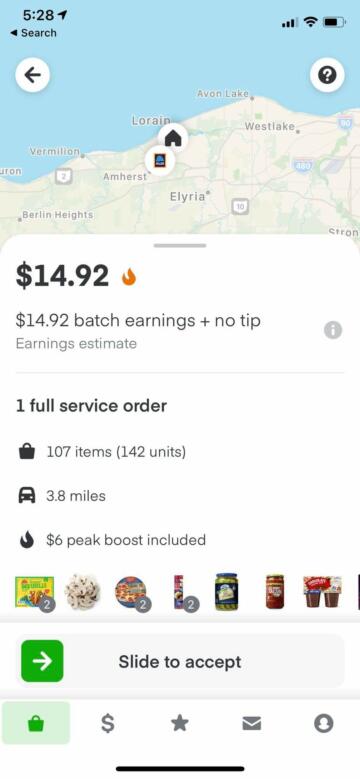

When workers open the app, they see available “batches” (Instacart’s nickname for grocery orders), which show a set commission price plus the customer’s tip. If the batch is higher paying, workers have around 30 seconds to decide whether to take it before it disappears. Workers say the $7 and other lower paying batches tend to sit there. Harris said batch prices can be all over the map.

“I’ve seen batches with 90 unique items for $7, and I’ve seen batches for 12 or 13 items for $7,” Harris said. “There’s no sense to it.”

Harris provided The Markup with several screenshots of batches in late September. One, for example, was for 107 grocery items and offered $14.92 total pay with no tip. Another was for four items for $22.94 and a $3.33 tip but included a 28-mile drive to the customer’s home. Several other screenshots also showed long drives, two batches bundled together for the same price, or orders with more than 100 items (which can take up to two hours to fulfill). All payments were within a $7 to $22 range.

In its demands, Gig Workers Collective is asking Instacart to reinstate three of its previous payment methods. It wants workers to be paid per order and the company to stop bundling batches together. It wants the per item payment reestablished, since orders with a lot of items take more time. And it wants Instacart to restore the default in-app tip to 10 percent, rather than 5 percent, where it’s set now. (Customers can choose their own tip amount; the default is a suggested prompt.)

We “removed the ‘none’ option in the customer tip settings, requiring customers to manually change their tip to $0 if desired and making it less likely that a customer will remove the shopper tip altogether,” Montalvo said. She added that, “We have a customer tip default setting which allows customers to save their default tip based on their last order.” Montalvo didn’t comment on Gig Workers Collective’s other demands around pay.

In the past, Instacart has said it wouldn’t raise the app’s default tip because it “serves as a baseline for a shopper’s potential tip and can be increased to any amount.” When the company changed its pay structure and stopped the $0.40 per item payments, it said that was to “provide clearer and more consistent earnings” for workers.

“Over time, it just started to deteriorate,” Solis said. “We feel those [demands] are reasonable…. They’re stuff that we had before, and we just want them back.”

What Else Do Instacart Workers Want?

Along with changing how Instacart pays workers, Gig Workers Collective is asking the company to adjust the rating system by which customers evaluate delivery workers. Currently, customers rate workers on a five-star basis, and Instacart can reward high scores by giving those workers first dibs on orders. Workers with lower ratings can get offered less lucrative batches.

“Shoppers’ access to batches is determined by a number of factors, including customer demand and shopper location,” Montalvo said. “If there are more shoppers than there are available batches, we’ll use additional criteria like timeliness, accuracy, and customer rating to determine access to batches.”

Workers say customers often ding them for things like sold-out grocery store items and slower delivery because of long lines or traffic. According to a Los Angeles Times article, some customers report missing or damaged items to get free or discounted groceries, and Instacart tends to blame the delivery workers in those situations.

“Even when we provide photos of deliveries, Instacart can either lower our rating (which prevents us from seeing good offers for weeks), or deactivate us from the platform entirely,” Gig Workers Collective wrote in its open letter. “Instacart’s inability to properly investigate customer complaints should not result in blame unfairly placed on shoppers.”

Montalvo said in cases when the company determines a customer has been fraudulent, the worker’s low rating in that instance may be “forgiven.”

Workers in Facebook groups, Reddit threads, and on Twitter often complain of being unfairly deactivated. Some say it’s possibly because their ratings dipped. Others say maybe it’s because they requested extra pay on heavy orders too many times. A couple of workers say they thought they were deactivated after their phone accidently took a photo in their pocket, which they believed Instacart thought was a fraudulent selfie check (something the company occasionally requires).

Gig Workers Collective’s final demand is for Instacart to provide workers with occupational death benefits—to help their families if something goes wrong. They say working for the company can be dangerous. Not only have workers tested positive for COVID-19, but they’ve also been robbed, assaulted, and had guns pulled on them. Lynn Murray, one of the people killed at a supermarket during a mass shooting in Boulder, Colo., was working for Instacart at the time.

Montalvo said the company offers “Shopper Injury Protection,” which “includes coverage for certain medical expenses, disability payments, and accidental death benefits.” She said workers can file claims directly with Instacart’s insurance provider. Montalvo didn’t respond to questions about how many workers have received the benefit. Instacart workers who spoke with The Markup said they’d never heard of the program.

Because Instacart classifies its workers as independent contractors, they don’t have employee benefits, like life insurance, health care, workers’ compensation, and sick days.

“This work is becoming increasingly dangerous,” Solis said. “We feel like we need basic protections.”

What Could Boycotts, Protests, and Strikes Accomplish?

Such collective actions have happened before, to mixed results.

When thousands of Instacart workers announced an emergency walk-off in March 2020 over inadequate personal protective equipment and sick leave, the company told reporters, “We’ve seen absolutely no impact to Instacart’s operations.” Yet, days before the strike, it changed its policy—pledging to send workers PPE kits and confirming 14 days of sick leave pay for those diagnosed with COVID-19.

Similarly, a year before, when Instacart workers filed a class-action lawsuit against the company for subsidizing their wages with customer tips, founder and former CEO Apoorva Mehta issued a rare apology and ended the practice. The case was resolved as part of a class action settlement. Workers have seen other changes because of their protests. At one point, Instacart had paid some workers as little as $1.50 per order, and the company raised those types of prices after workers spoke out.

“The companies never want to admit that if they change a policy, it’s because workers are demanding it,” said Rutgers’ Givan. But “Instacart workers’ organizing skills get sharper and sharper as they build a movement.”

While Instacart has made concessions in the past, however, workers say they still haven’t seen the structural changes they’ve long demanded.

“With our protests, they don’t have the immediate effect that we want them to—but they do have an effect,” Solis said. “That’s why we continue to do it.”